4 elements of kindergarten transition programs to alleviate disruptive behavior

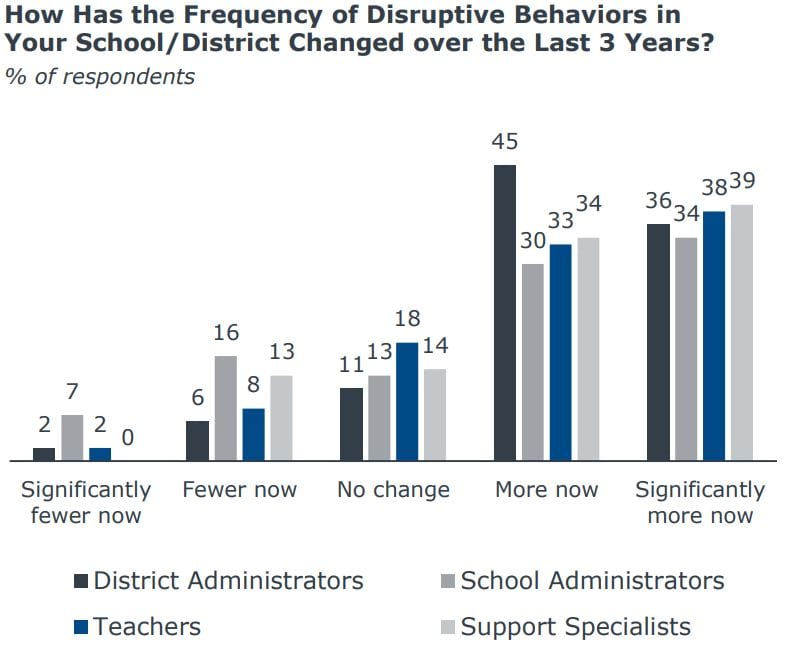

Over the past few years, educators across the U.S. have expressed concern over a perceived dramatic rise of behavioral disruptions in early grades. This perception holds steady across various school and district roles, ranging from district administrators to teachers. In fact, more than a third of all respondents in EAB’s recent national survey on behavioral disruptions note that misbehavior has increased “significantly” during the last three years.

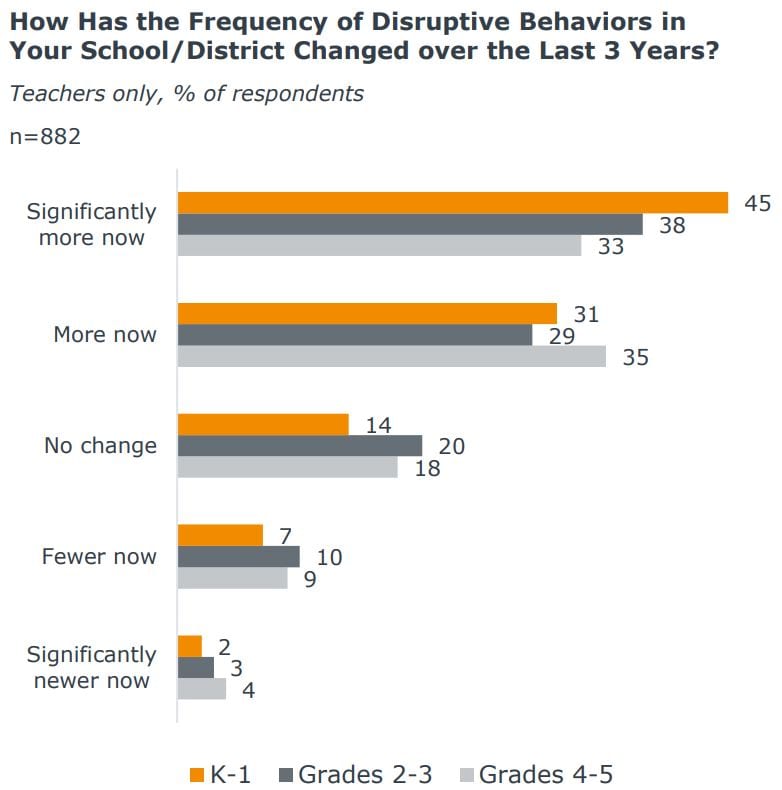

Taking a closer look into teacher responses reveals that disruptions are particularly prominent in the earliest years. Seventy-one percent of all elementary school teachers (K-5) believe behavioral disruptions have increased over the last three years. This number is even higher among kindergarten and 1st grade teachers (76%) than among teachers in grades 2 and above (67%).

Most incoming kindergarteners not well-prepared for school

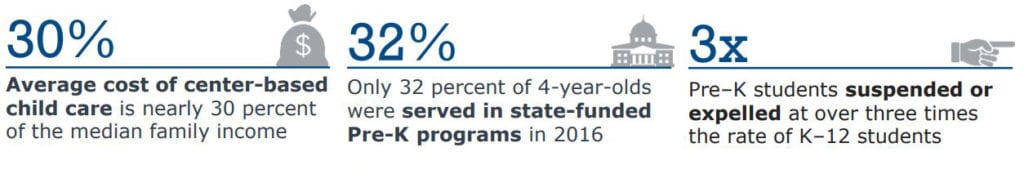

Research on national trends in early childhood education suggests that for many young learners, kindergarten may be their first exposure to a structured learning environment. The most common reasons for this are poor access to center-based child care and the tendency of many public and private early learning institutions to suspend and expel “disruptive” children without providing sufficient support to improve the child’s behavior.

Regardless of the causes, public schools are enrolling a growing number of students who do not have the social-emotional skills needed to succeed in kindergarten and beyond. To address this issue, many districts are developing summer transition programs that focus on building the social-emotional and behavioral skills of incoming kindergarteners and acclimating them to a structured educational setting. These programs mimic the structure and routines of kindergarten, but focus exclusively on routines, procedures, behaviors, and understanding and expressing one’s emotions.

Kindergarten transition programs an effective form of early intervention

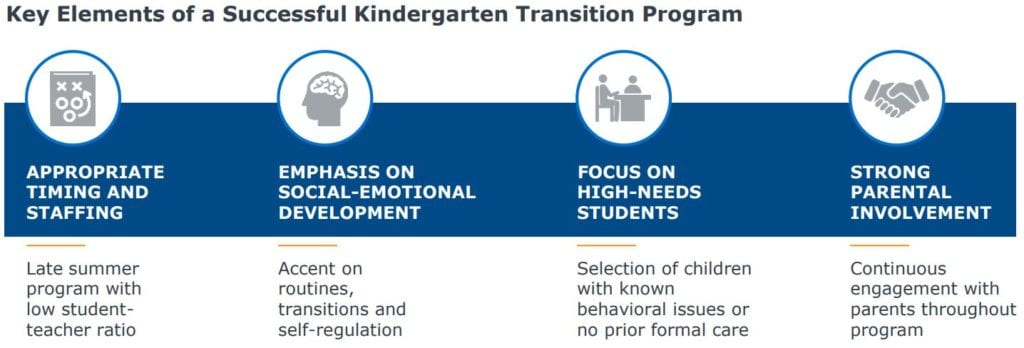

We spoke to multiple districts that created such camps and identified the four key components of high-quality transition programs that develop the social-emotional skills of students to better prepare them for success in school.

Sources: Gilliam, W., “Pre-Kindergarteners Left Behind: Expulsion Rates in State Pre-K Programs,” Yale University, June 2010; Barnett, W.S. Friedman-Krauss, A. Weisenfeld, G.G. Horowitz M. Kasmin, R. Squires, J.H., “The State of Preschool 2016,” The National Institute for Early Education Research, 2017; Workman, S. Troe, J., “Early Learning in the United States: 2017,” Center for American Progress, 2017; EAB interviews and analysis.

The first key element of transition programs is the appropriate timing and staffing of the program. Students often act out because they don’t feel secure and familiar with their environment and frequent transitions from one setting to another exacerbate the problem. Scheduling the program in the week(s) immediately before school starts reduces those transitions and gives children time to get used to the structure of kindergarten.

The people best-suited to provide social-emotional learning support and guidance are kindergarten teachers with strong expertise in the area. Selecting camp teachers from among a district’s best SEL educators (as indicated by peers or principals) and ensuring low teacher-to-student ratio (1:10 or lower) makes the most out of the time students spend in camp and allows them to quickly build up the skills they need.

The second key element is keeping the focus on social-emotional learning and resisting the temptation to add academics. The camp is targeted at students with known or potential behavioral risks, not ones with learning difficulties. Students should be taught routines, rules, understanding and expressing emotions, and interacting with peers, while teachers should select materials to reinforce these skills. A good social-emotional learning program provides children with a mixture of predictable routines, group activities to build communication and collaboration skills, as well as free time and physical activity to help children practice those skills independently.

Third, in order to make the best use of the program, administrators should enroll the students who would benefit most. Through a mixture of advertising in the community and working with parents and local childcare centers to identify at-risk children, program leaders should consider students with the greatest need for support. This may include children with known adjustment or behavioral issues, or those who have been identified by their parents as having frequent and extreme tantrums. Another important group to recruit is students who have never attended daycare or preschool, or who were placed on wait lists for programs such as Head Start.

Finally, engaging parents is critical to ensuring the benefits of the program extend into the school year. Administrators should set up observation sessions and teach parents how to reinforce positive behavior at home in order to truly improve students’ behavior. Program leaders should also solicit parents’ feedback both at the end of the program and during the school year, in order to make appropriate changes to content or logistics and ensure the camp meets its goal of teaching students long-term social-emotional skills.

Although such programs can be somewhat resource-intensive, early evidence from successful districts demonstrates that they are both very popular with families and that they successfully reduce and mitigate instances of student dysregulation in both kindergarten and first grade. Districts that are worried about a growing population of students exhibiting disruptive behavior should strongly consider building a summer program that focuses on building critical social-emotional skills among the youngest learners.

More Blogs

From building managers to strategic leaders

From cell phones to STEM: What district leaders are focused on right now