Why even C students should consider taking 15 credits their first semester

Please note, this post has been updated to include methodologies and additional guidance for policymakers.

How should you advise an incoming student who is registering for their first term in college? Would you recommend that they take 15 credits to stay on track for a four-year graduation? Or should they ease into their first term, taking only the full-time minimum of 12 credits, and make up the difference later?

What if I told you that student had a dubious high school record or would be working significant hours while taking classes—would your advice change?

I often hear from advisors and administrators the desire to protect their new students from overwhelming themselves with coursework in their first year, especially if it seems like the student would benefit from the chance to adjust to college life—and many students think the same way. As a result, 44% of incoming full-time students average just 12-14 credits per term during their first year, less than the 15 they need to stay on pace for four-year graduation. That extra time in college comes at a cost, both in tuition and in the opportunity cost of delayed entry to the workforce.

How the University of Hawaii’s campaign improved student outcomes

Recently, many schools in the Student Success Collaborative have adopted “15 to Finish,” a public relations campaign that promotes the academic and financial benefits of taking more credits and finishing in four years. They are following the lead of the University of Hawaii, the first school to deploy the “15 to Finish” messaging strategy. UH has seen meaningful results—in just one year, the majority of incoming full-time students at UH shifted from taking 12 credits to taking 15 or more.

Before launching the campaign, administrators and advisors at UH sought to ensure that the extra coursework wouldn’t harm their students. Analysis of historical records verified that incoming students of all backgrounds and academic achievement levels performed just as well on average when taking a 15 credit course load.

Since the “15 to Finish” philosophy is becoming much more widespread, we sought a national analysis to see if the findings from UH held true for other students and schools. We examined data from 1.3 million incoming full-time students representing 137 schools in the Student Success Collaborative and compared outcomes for students who averaged 12-14 credits per term across the first year to those averaging 15 or more. Here’s four essential insights we found:

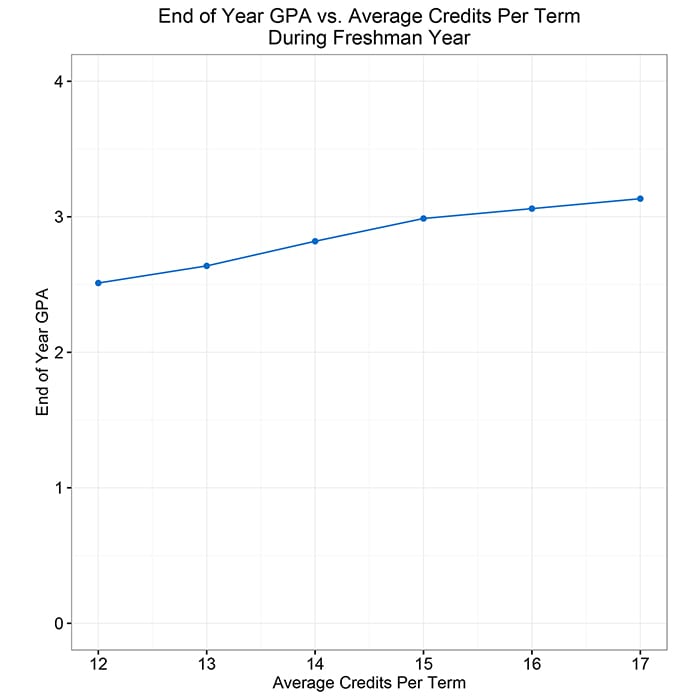

1. We confirmed that students who average 15+ credits across their first year end the year with higher GPAs and higher retention rates than their full-time peers who take fewer credits. These students ended their first year with a GPA that was 0.36 grade points higher than their peers (3.04 versus 2.68) and were retained at a rate nine percentage points higher (90% versus 81%). Not only were these students not suffering from the additional course load, they were thriving.

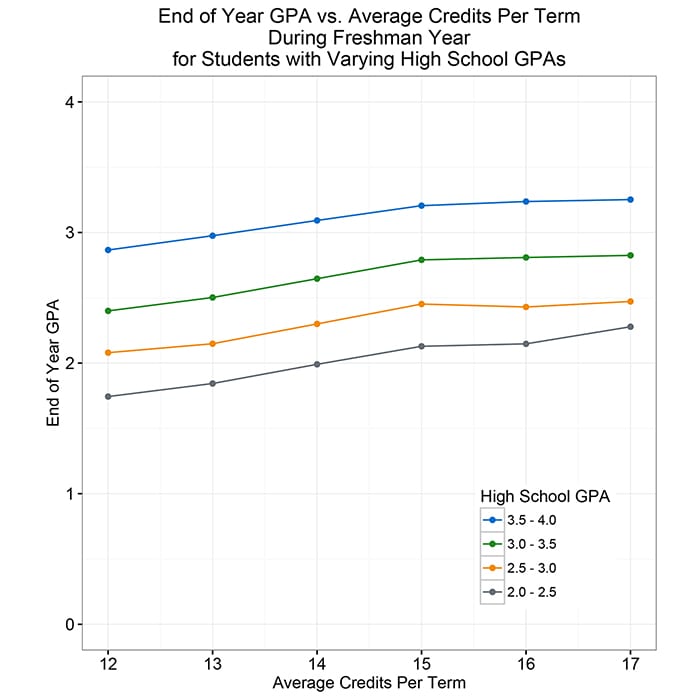

2. Students at all levels of academic achievement benefit from taking 15+ credits. To ensure that our initial finding was not simply the result of better students taking more courses, we repeated our analysis controlling for students’ high school GPA. We found that students of every level of high school academic achievement experienced better first-year GPA and retention outcomes when they took more courses. Even students with a high school GPA between 2.0 and 3.0, who averaged at least 15 credits, were two percentage points more likely to persist than their peers that only took 12-14 credits. They also ended their freshman year with a GPA that was more than a quarter of a grade point higher.

3. Low-income students also benefit from taking 15+ credits. Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to be working large numbers of hours in addition to taking classes. Some advisors have wondered if a 15+ credit schedule made sense for many of these students, given the constraints on their time. Although this is something that each student should decide for themselves, the general trend holds true for low-income students as well. Using the Pell grant as a proxy for family income, we found that Pell students who took 15+ credits were seven percentage points more likely to persist and had an end-of-year GPA that was 0.12 points higher than their Pell recipient peers who averaged only 12-14 credits per term in the first year.

4. Early course-taking behaviors seem to be habit-forming. Students who take 15+ credits in their first term average 15.9 credits per term for the remainder of their college careers, while students who take 12-14 credits average just 13.5, the difference of nearly one three-credit course every term. Nearly one in six students who take 12-14 credits will never take a 15+ credit load. This suggests it is incorrect to assume that students who “underload” in their first term will pick up the pace once they settle into college.

Most schools that initiate “15 to Finish” programs offer flat-rate tuition for all full-time students taking above 12 credits. If your school does not have flat-rate tuition, you should take into consideration the impact that the cost of taking additional credits might have on financial aid and a student’s’ overall ability to pay, as well as offering students and their families additional guidance as part of the messaging campaign. Most schools that do not offer flat-rate tuition are still likely to find that students will save money in the long run by taking more credits each term, although the overall savings might be muted.

Advice for policymakers

Many states and schools are grappling with potential policy shifts to graduate more students within four years. Based on best practice research, prior analyses, and this nationwide study, we believe that policies encouraging students to take 15 or more credits per semester should be closely considered. The findings from this analysis echo what many schools have seen on their own campuses and could be a helpful complement to an institution’s own comprehensive analysis, which can be tailored to include local factors.

That said, the available data only allowed us to include a limited number of variables, and we were not able to account for every potential covariate. We do not advise schools to make a policy shift based purely on this analysis. Instead, our goal is that these findings will move students and schools away from the common generalization that certain subsets of full-time students should not take 15 credits per semester.

Students, no matter their academic preparedness or financial situation, should consider taking 15 credits per semester—and then work with their advisor to make the decision that makes the most sense for them.

Methodology

The EAB Data Science Team (Ali Bagherpour, PhD; Charles Carbery; William Heath; Janek Nikicicz; Ankur Roy; Lars Waldo; and Jeremy Werner, PhD) conducted an observational analysis of the academic record data of nearly 1.3 million freshmen from 137 colleges and universities representing a broad array of American public and private institutions. The analysis cohort included all full-time freshmen who started college at these institutions between summer 2011 and spring 2016; neither part-time nor transfer students were included in the analysis cohort. Only regularly-scheduled terms were included in the calculation of average credits per term during freshmen year; e.g., credits taken during summer terms were excluded. Likewise, any AP credits a student may have brought with them to college were excluded.

Of the nearly 1.3 million full-time freshmen included, 56% enrolled in at least 15 credits per term on average during their freshman year, while the remaining 44% enrolled in between 12 and (just under) 15 credits. Four different outcomes for these freshmen were considered: retention to the sophomore year, end of freshmen year GPA, credits taken per term in subsequent years, and, in the case of students who began between summer 2011 and spring 2012, graduation within four years. The mean average of these outcomes were measured for various subgroups of students, defined by their average number of credits enrolled in per term during their freshmen year, cumulative high school GPA, and, for a small subset of these students, whether they were Pell grant recipients.

The cohort of the Pell analysis was limited to the roughly 18,000 freshmen from six private institutions that Pell data was available for. Four thousand of these freshmen were Pell recipients and 14,000 were not.

More Blogs

Why advising reform can’t wait—and what colleges and universities must do now

How Thematic Major Clusters, Major Maps, and Faculty Mentorship Elevate the Student Experience