Here’s how to answer common faculty workload questions

In recent discussions with academic leaders, uncertainty around instructional staffing is a common theme. Many are unsure of how to best set faculty workload expectations and ensure that resource allocation meets demand.

Colleges and universities know that they could boost cost efficiency by asking their full-time faculty to teach more, but they often struggle find the right workload. At the same time, they need to ensure that resources are keeping pace with demand for each discipline. To inform these decisions and have productive conversations, leaders need to come prepared with data.

Recent analysis of the Academic Performance Solutions (APS) benchmarking data gives campuses a starting place to compare faculty workloads to peers and anticipate shifts in student demand.

Question: Should we adjust workload expectations for full-time faculty?

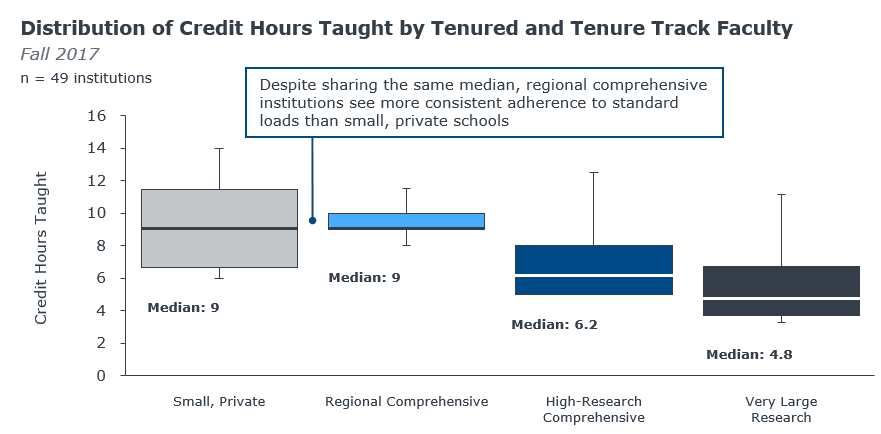

This is often the first question EAB gets when sharing APS faculty data—and there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Each college or university needs to consider their own mission, but using cohort benchmarks can help institutions compare teaching activity to peers with a similar emphasis on research or teaching. For example, full-time instructors at colleges or universities with greater research expenditures typically teach less than five credit hours per term, in contrast to the higher teaching loads of nine credit hours per term at institutions with little to no research expenditures.

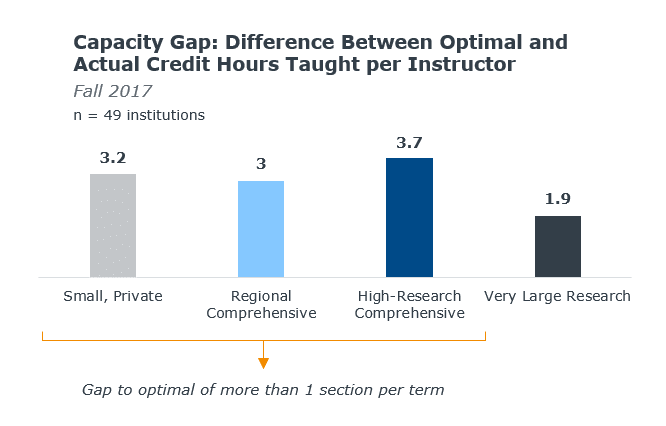

To determine if you’re fully utilizing existing instructional capacity, or if you may want to consider adjusting workload expectations, you first need to identify an optimal output. When using the 75th percentile of credit hours taught for each of the APS cohorts as the optimal capacity, we found that more than a third of colleges and universities use 80% or less of their capacity. On average, institutions have a gap of more than three credit hours per term per instructor.

When an institution or department’s actual number of credit hours taught by full-time faculty exceeds the optimal number, it begs the question: Are adjunct hours being used or are our full-time instructors overloaded? Alternatively, when an institution or department’s actual amount falls short of the optimal, this may warrant shifting some credit hours away from adjunct faculty and instead of toward tenured and tenure-track instructors.

Question: Do we have the right instructors teaching the right students?

When discussing maximizing instructional resources, academic leaders also want to know how well they’re keeping pace with changing demand from students. Over time, colleges and departments will experience shifts in demand for certain programs and courses and adjusting capacity for the short- and long-term can prove challenging. Disciplines in the arts and sciences, for example, continue to experience significant enrollment declines and must align faculty workloads accordingly.

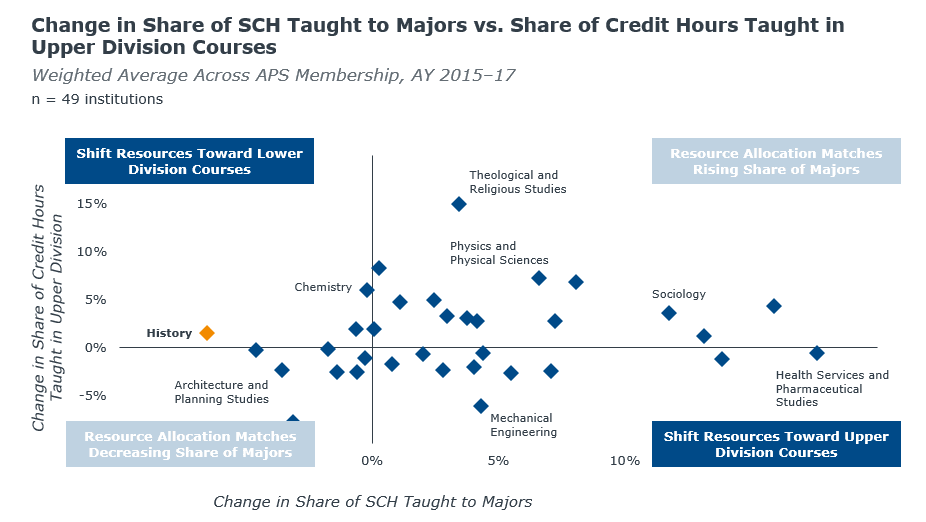

Beyond shifts in enrollment, departments may also need to address shifts in their own mission—stemming from trends in demand among majors versus non-majors. If, over time, a department teaches a greater share of its attempted student credit hours to majors, department leaders may consider shifting instructional resources toward the specialized, upper division courses. On the other hand, if a department is teaching a lesser share of its attempted student credit hours to majors, it should consider shifting instructional resources toward lower division courses to accommodate non-majors taking general education courses.

To diagnose where resources are needed, or where there may be excess capacity, we plotted the change in share of credit hours taught in the upper division courses against the change in share of attempted student credit hours (SCH) taught to majors. We found that about half of the departments in our benchmarking data—including history departments—are allocating resources in a way that is incompatible with shifting demand.

History departments, on average, are experiencing declines in enrollment from majors, yet they have overall increased investment in upper division courses. To get instructional capacity aligned, departments in this circumstance need to further analyze the course offerings and faculty assignments to ensure that there is not excess capacity within specialized, upper division courses.

More Blogs

Was the impact of remote instruction as bad as we feared? Here’s what the data shows

Q&A: Why one university brought data strategy into the cabinet