Is your student success strategy ready for the next decade?

In the aftermath of the Cold War, the US military coined the term VUCA (which stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity), to describe new and unstable environments. Since then, the term has been widely adopted in strategy and management circles—but I would posit it’s also very relevant to us in higher education. VUCA environments are scary for leaders since they challenge the status quo, but they also represent opportunity for organizations that can ride the wave and innovate.

Read on to understand the challenge and learn what you can begin to do to respond.

As we approach the dawn of a new decade, higher education is entering perhaps the most volatile and uncertain environment any of us have seen in our careers. There are many expressions and consequences of VUCA in higher education, but for those of us in the student success space, no measure of volatility will matter as much as that caused by the shrinking size of our traditional population of 18 to 22-year olds, and their tuition checks on which we are now dependent.

This is nothing new to private colleges and universities, who have always been tuition dependent and seen their fortunes rise and fall along with the supply of college-going high school graduates. Public colleges and universities, on the other hand, have until recently enjoyed a steady stream of state funding to serve as a buffer against secular ups and downs in enrollment. Recent state divestment from higher education has eliminated much of that buffer, leaving the publics just as exposed to population trends as their private sector cousins.

Forecasting the challenges of the next decade

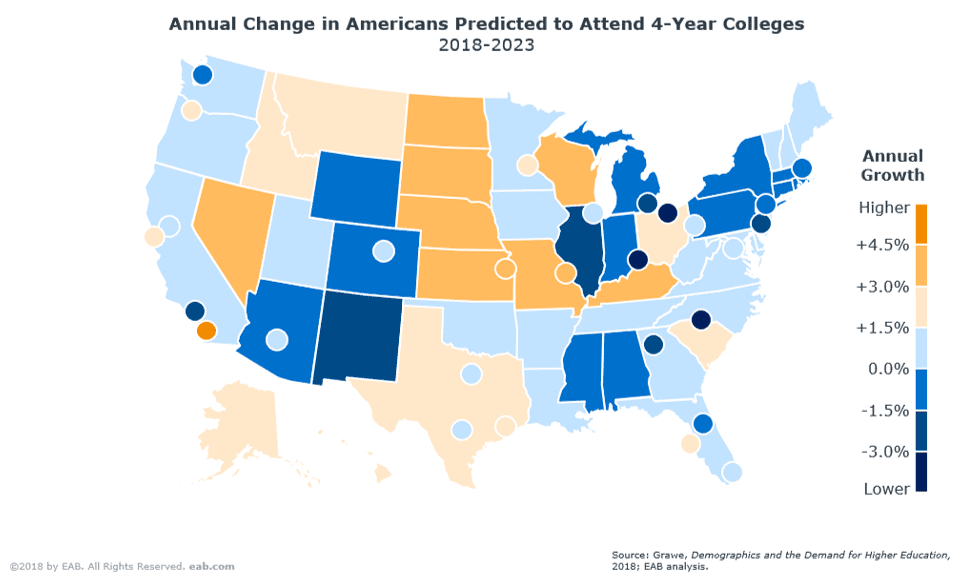

These enrollment changes will be felt less or more strongly depending on where in the country you are located. The best work to date on this can be found in Nathan Grawe’s Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education. In it, Grawe uses data from the US Census to makes state- and city-specific forecasts of the number of college-going high school graduates through the end of the 2020s.

Grawe shows that most regions of the country enjoyed an enrollment boom throughout the 2000s. This boom is now over. Major areas of the Northeast, Midwest, and Mid-Atlantic are currently or will soon experience a precipitous decline in the number of college-going high school graduates. The situation will become especially dire toward the end of the 2020s as the cohort of children born during the low birth-rate years of the Great Recession become college aged. Even the current high-growth areas in the Southeast and California, will be affected.

Grawe’s enrollment projections assume that student preferences and behaviors do not change and Gen Z will continue to choose colleges in the same way as their Millennial predecessors. This may not be true. Gen Z are the frugal sons and daughters of the Great Recession, and there is growing evidence they are seeking cheaper college options. Notably, we’ve seen some early evidence that Gen Z students from affluent and very affluent backgrounds are turning down four-year acceptances to instead attend two-year schools with the intention of completing inexpensive coursework before moving on to a bachelor’s degree. If this becomes a trend, it could provide some small enrollment relief for the two-year space while compounding the problem for the four-year schools.

Higher education as antifragile

The coming enrollment challenge certainly seems bleak. But might this difficult time actually be good for higher education? Author Nassim Nicholas Taleb recently coined the term “antifragile” to describe structures and system that benefit from volatility and uncertainty. Much like the Hydra of Greek mythology or the skeletons in our body, antifragile systems not only survive being stressed, they actually become stronger because of it.

I think higher education might be one such antifragile system.

As the millennial generation wanes into the smaller Gen Z, competition for prospective students will reach new heights and new levels of expense. Every possible market will be tapped, including transfers, internationals, adults, non-degree seekers, and other post-traditional demographics. As recruitment costs soar, many schools will redouble their retention efforts in order to protect their investment.

Student attrition also costs colleges and universities tens of millions of dollars in lost tuition each year. The loss is compounded when you realize that a lost sophomore also represents the loss of a potential junior and senior in future years. With new students increasingly difficult to come by, the most important (and least expensive) recruitment pool might be the students that are already enrolled on your campus.

Can Student Success Management help?

Viewed this way, student retention is no longer just the right thing to do, it is also an important measure for ensuring the financial health of your institution. Progressive schools have realized this and are beginning to respond. Indeed, over the last few years, EAB has documented a new family of student success practices, called “Student Success Management,” or SSM, characterized by proactive outreach, technology enablement, and fast-cycle metrics that can help leaders track progress against core KPIs in real time. Many SSM practices track the fast-cycle metrics for registrations and next-term enrollments that can be directly tied to revenue, much as your admissions office always has a real-time count of the number of applications and matriculants.

These financial gains are great, but the benefits for students are even better. Indeed, there’s growing evidence student success management practices can help schools realize 2-4% gains in persistence within one year of implementation. We will dive deeper into these practices in the next two posts in this series.

Innovations in Student Success Management will help make higher education antifragile. As enrollment stressors increase, schools will be forced to get better at retaining students simply as a matter of self-preservation. Our responses to enrollment stressors will make us stronger at retaining students, and ultimately result in more students graduating. This is a win-win for student and school.

Nobody feels perfectly comfortable in a VUCA environment. But I am optimistic that our immediate response to the challenge ahead will ultimately make institutions better equipped to retain and graduate today’s students. The lessons we learn about strategy, management, and student success in the coming years will persist even when enrollment projections improve, proving out the antifragility of the system. It’s now up to us to forge ahead to learn these lessons, together, and to do so quickly.

More Blogs

Career readiness can’t wait until junior year

What matters to student success teams in 2026