Few industries have been as hard hit as restaurants in the pandemic. But alongside widespread closures of franchises and family-owned establishments, restaurants have also become the site of rapid business model innovation: there are the reinvented patios and “streateries” lining the streets of cities; the Korean take-out spot, temporarily turned “mobile bodega,” delivering bleach and hand sanitizer overnight; and the restaurants offering virtual experiences to accompany take-out orders, like meeting the fisherman who caught the sushi-grade tuna on the tray.

Colleges and universities face their own tough reckoning this fall—with some institutions already suspending plans for in-person instruction and more schools likely to follow in their footsteps. What can higher ed learn from the restaurant industry, not only in how to pivot quickly in a crisis, but about competition, market positioning, and strategy for the long-term?

1. Will higher ed competition become winner-take-all?

With more students than ever enrolling in online or newly remote programs during the pandemic, some have speculated that online mega-universities and national elites will soon take over higher ed. What could this mean for master’s programs, where already the most growth has been happening in online programs while face-to-face enrollments steadily decline? Are we at the dawn of a winner-take-all era?

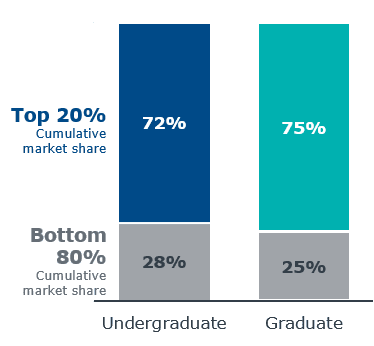

Here’s the good news: winner-take-all competition doesn’t dominate higher ed yet. It’s true that the top 20% of institutions confer about 75% of the degrees—both in grad and in undergrad. And some grad programs, like computer science or cybersecurity, are highly concentrated with a small proportion of institutions conferring most of the degrees.

Institutions with Highest Conferrals Control Most of the Market

Percentage of total degrees conferred by top 20% of institutions, 2018

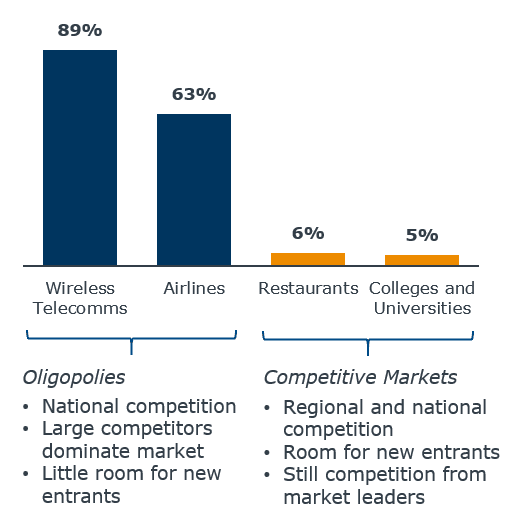

But when we look at competition in other industries, higher ed doesn’t look all that concentrated. For airlines and telecoms, the top four competitors (not surprisingly) capture most of the revenue in the U.S. By contrast, in higher ed, the top four competitors bring in only about 5% of the revenue. Competition in higher ed actually looks a lot more like competition in the restaurant industry than it does in the airline industry.

Higher Ed is not an Oligopoly, but Still Faces Dominant Market Leaders

Market Share of Top 4 Competitors by Industry (Revenue)

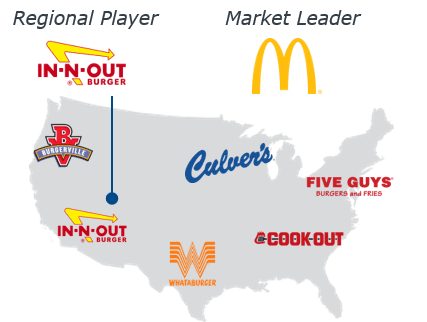

While restaurants look and operate a lot differently now than they did five months ago, their competitive context still looks similar to what it was before the pandemic. Restaurants face local, regional, and national competition all at the same time. They can’t afford to think about only their local competitors. A choice as simple as where to get a burger and fries illustrates how this works.

When the craving for a burger and fries hits, most people have a range of similar options: a large national chain like McDonald’s, a regional favorite like Culver’s in the Midwest, or local diners and “mom and pop” stands. It’s true these restaurants don’t serve the exact same products. And while we could debate the relative merits of getting a meal from McDonald’s (childhood memories) or Culver’s (frozen custard on the side), both of these places still deliver the same basic satisfaction.

Mass Market Leaders Limit Potential for National Growth

Regional Players

- Strong regional brand affinity

- Large online and on-ground presence

- Low cost or elite brand

Market Leaders

- National marketing reach

- Massive online scale

- Low cost

Of course, the decision of where to get a burger and fries is nowhere near as important, expensive, or complex as the decision about where to enroll in a grad program, but the analogy is still useful here. Just as with restaurants, it’s not the case that colleges and universities are either up against powerful online mega-universities or competitive regional and local brands for enrollments in grad programs—it’s that all of these things are true at the same time.

Colleges and universities face big national players marketing in their backyards as well as competition from strong regional higher ed institutions and other local institutions embedded in their communities and industries. Students could just as easily choose a “mass market” offering, especially when aggressively recruited, as they could a familiar and trusted local option.

Align your strategy to the market

Here’s how to revise your strategic plan now to ensure long-term sustainability.

read the insightIn the coming year, the pandemic will only intensify this competition in the higher ed grad market, especially as institutions look beyond their usual markets to recoup lost revenue from international students and undergraduates. Colleges and universities should anticipate more unexpected competitors and a wider range of competitors, making it all the more important for every institution to reassess who its competitors really are, which competitors and programs pose the greatest threat, and whether these competitors have already changed during the pandemic.

2. Is it better to be similar or distinct?

A successful restaurant looking to expand its footprint has an important decision to make: should it establish a franchise or develop a restaurant group? At its core is a fundamental question: Is it better to replicate the same restaurant over and over, providing consistency and familiarity to a growing customer base like McDonald’s? Or is it better to create different menus and experiences to cater to different groups of customers and types of occasions, like Darden Restaurants, which includes both The Capital Grille steakhouse and Olive Garden?

Colleges and universities often face criticism for trying to be “all things to all people.” Within state systems especially, there is increased scrutiny on duplicative offerings and pressure to create distinct identities for each institution in the system. But private institutions in saturated markets feel these pressures too.

In the drive to differentiate, institutions often hope for a first-mover advantage—and there are many opportunities for this in the pandemic. For example, advantage will go to the institutions that provide significant virtual experiential opportunities to every single student, or deliver ultra-low-cost degrees at both the undergrad and grad level, or offer success coaching for students during and after graduation.

From Ambition to Strategies

10 Ways to Differentiate While Meeting Our Highest Aspirations

Unquestionable Return on Investment

1. Radical affordability

2. Experiential learning at scale

3. Institution-wide focus on outcomes

True Engine of Upward Mobility

4. Seamless institutional pathways

5. Mass personalization of the customer experience

6. Integrated mental health and wellness

7. Radical flexibility

Recognized and Valued as Public Good

8. Reaching underserved adult markets

9. Strategic professional program growth

10. Cross-sector regional economic development

But all too often institutions assume that strategic differentiation automatically confers an advantage. In some cases difference can be a detriment, particularly when what is on offer looks unfamiliar or risky to students. Take the case of competency-based education. Five years ago, many hoped that competency-based programs that prioritized skills over time-in-seat would appeal to adult learners hoping to earn their degrees quickly. What most institutions quickly learned was that few students knew what “competency-based” meant, and even fewer were willing to take a gamble on unfamiliar and untested program offerings. Even Western Governor’s University, a pioneer and the biggest provider of competency-based programs, shifted its marketing to downplay “competency-based” and emphasize “flexible, affordable” degrees instead.

In some cases there can be advantages to resembling the institution next door, but colleges and universities shouldn’t overlook market opportunities and student demand to evolve their experiences.

3. What are the real “jobs to be done”?

In early June, as shutdown restrictions eased across the country, McDonald’s ran a new TV spot called “More Than an Order.” It began with the tagline, “this order could be more than an order” and went on to explain that the McChicken sandwich on the screen wasn’t just a McChicken sandwich. For someone emerging from three months of lockdown, the McChicken sandwich was a lifeline to society: it could be the first meal eaten with another person in a long time, the first meal eaten while not wearing pajamas.

It’s a perfect, 15-second illustration of Clayton Christensen’s concept of Jobs to Be Done. This is the idea that people don’t buy things because of their surface value or stated value proposition—they buy things to meet deeper unstated needs. His classic case study is a fast food chain looking to sell more milkshakes. Christensen’s team found that most milkshakes were purchased in the morning and the late afternoon—not as a sweet treat after lunch or dinner. After observing and talking to consumers, they discovered that people were buying milkshakes in the morning to make their commutes less dreary. Fathers were buying milkshakes for their children in the afternoon, a way of saying “yes” to a treat after a long day of having to say “no” to their many wants.

These insights about the actual “jobs” that a milkshake can do opened up new business opportunities for the restaurant hoping to sell milkshakes: add coffee to the milkshakes for the commuters, and create special kid-sized milkshakes for the afternoons.

For many colleges and universities no longer able to deliver a traditional college experience this year, the question of “what are the jobs to be done” for a college degree has taken on new urgency. Are students and parents buying degrees or are they really buying something else? And if what they are really buying is something deeply connected to the in-person college experience, colleges and universities need to act now to invest in recreating those experiences virtually. The potential other “jobs” of a college degree include:

Related podcast

Hear what 100+ university presidents imagine for the future of higher ed.

listen now- Building a lifelong peer network

- Finding a mentor

- Getting out of the family home

- Coming of age

- Learning how to be an active citizen

- Exposure to more diverse perspectives

- Access to a job market with potential for career advancement

What would it look like for an institution to invest in performing these underlying “jobs” for students during the pandemic in addition to virtual instruction? And what is the revenue opportunity or competitive advantages for institutions that double down on new models for the student experience?

4. What if we could rebuild from scratch?

For about a week in May the number one article on the New Yorker website was “The Case for Letting the Restaurant Industry Die.” It profiled the work of an activist, artist, and cook named Tunde Wey, who argued that most restaurants are built on deep inequality, low-wages, and are rife with racism and sexism. Wey asked, why try to preserve the status quo when the pandemic could wipe out the industry and let everyone start over?

While it’s difficult to apply these extreme arguments to higher ed, Wey’s stance on restaurants raises the idea that the pandemic presents a unique opportunity to question what colleges and universities should preserve and what should be remade anew. Across institutions, retention and graduation rates haven’t moved much in the past ten years, 35 million adults have stopped out of school, and as the civic unrest of this summer has shown, most institutions have fallen short of their goals to deliver on social justice and economic mobility.

If we could start from scratch, what would it look like to design a college or university to solve these fundamental challenges? New institutions launched in the past twenty years already hold clues to the radical models that could be possible in the future:

- Harrisburg University of Science and Technology in Pennsylvania was founded in 2001 and operates without departments, deans, or tenure. It recruits and serves vastly more students from under-represented populations than other STEM-focused institutions, and its success in recent years has driven a regional turnaround.

- University of Minnesota – Rochester is a health sciences-focused institution that houses all of its faculty in the same department: the Center for Teaching and Learning Innovation. Uniquely, all faculty research focuses on pedagogy, with findings applied real-time in classrooms.

The day-to-day demands of responding to the pandemic make it harder than ever for colleges and universities to ask, much less answer, urgent strategic questions about the future of their institutions. But the need for higher ed to embrace institutional transformation in the face of competition and disruption could not be greater.

In the Higher Education Strategy Forum we partner with presidents, cabinets, and boards to facilitate workshops to quickly adapt strategic plans and develop bold, long-term future visions. Reach out to your EAB strategic leader to schedule a Strategy Pivot or Visioning Workshop session with your board or cabinet.