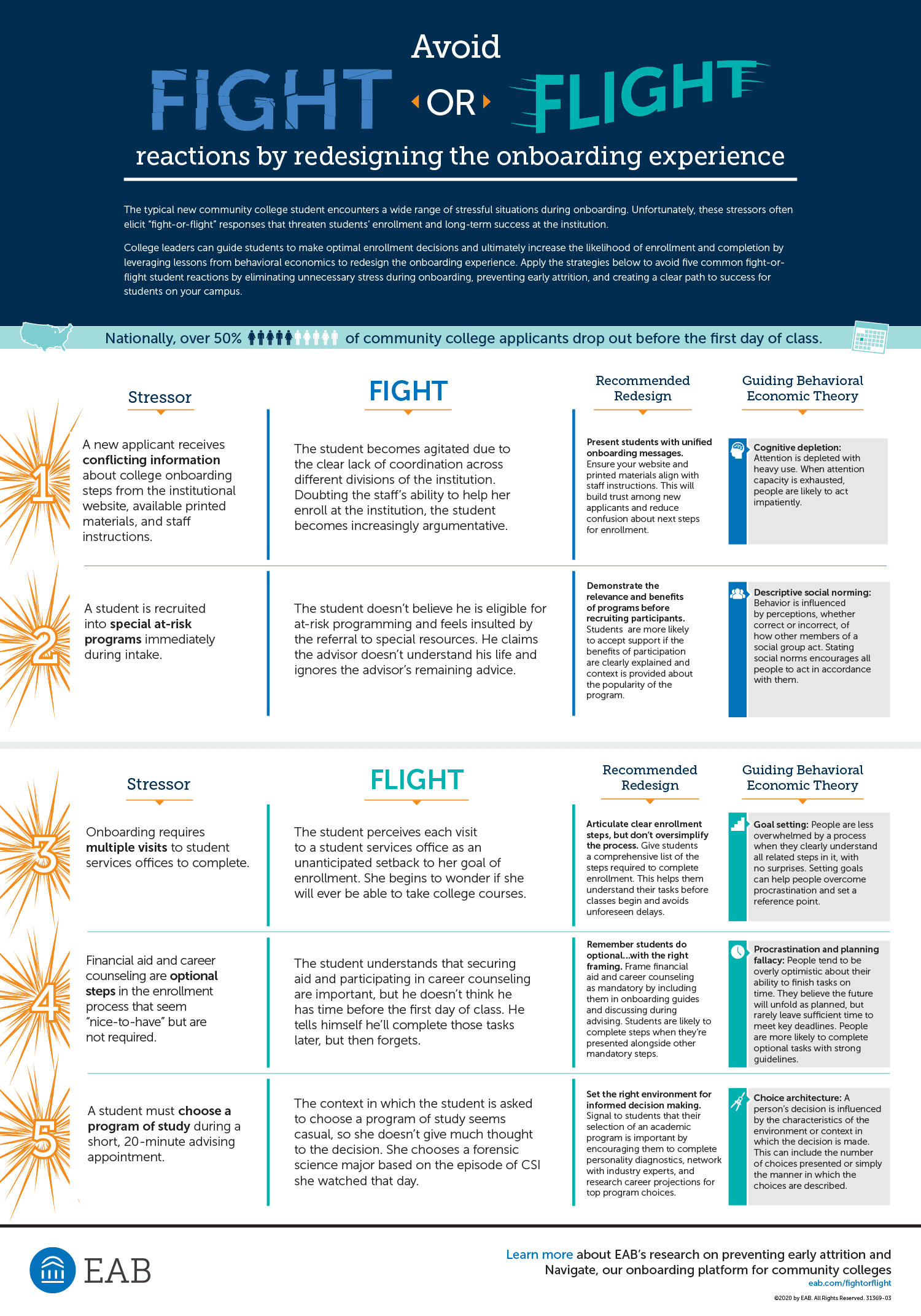

Avoiding ‘fight or flight’ behaviors in student onboarding

Evolutional biology in our hallways

In periods of intense stress, humans and animals exhibit a “fight or flight” response, which evolutionary scientists explain is a primitive, automatic, and inborn response preparing the body to either fight or flee from a perceived threat. The credibility of the threat is entirely in the eyes of the beholder; a crash in the next room can trigger this response whether caused by an intruder or merely a gust of wind.

Our research teams have interviewed hundreds of community college students over the past few years and found that every student who submits a college application, regardless of his or her background, has the same basic goal: take a class at your institution. But when students encounter a barrier or threat to that enrollment goal, they often react by fighting or taking flight. Anything from unexplained delays, seemingly unnecessary tasks, and complex decision-points wrapped up in strange language can trigger this response. The “fight” response is likely familiar: students who become increasingly frustrated with the process and try to bully their way through the enrollment process with yells and screams. This is rare but damaging for staff morale.

The “flight” response is more nuanced, as it manifests in one of two ways. The first is that applicants simply drop out of the enrollment process. Unfortunately this happens far too often, with about half of all community college applicants stopping out before ever stepping foot in a classroom. When students exhibit the second manifestation of the “flight” response, they retreat from a task by skipping it or investing the least amount of energy to complete it. One student told us that her goal of taking classes at her local community college felt like it was slipping away throughout the onboarding process—just as she started to make progress, she was hit with another step that would take time to complete, like filling out a financial aid application, or a decision she didn’t feel confident about, like choosing a major. Her stress levels were through the roof.

This student, like so many others, retreated (or “took flight”) from these decisions: she opted out of applying for financial aid and remained an undecided student for the first year of her enrollment at the college. While she was able to make it to the first day of class and realize her short-term goal, these decisions set her up for a long and troublesome time at the college.

Eliminating the threat?

By now the City University of New York’s (CUNY) Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) model is well known in the two-year college sector. CUNY has managed to show remarkable gains in semester-to-semester retention, credit accumulation, and graduation among participants. It’s an ambitious program with many components that are arguably difficult to scale because of resources and costs.

It’s no secret that the program also costs CUNY more than a million additional dollars per year. One of my favorite moments during this year’s AACC conference in San Antonio, Texas, was hearing CUNY LaGuardia Community College’s president Dr. Gail Mellow admit that the program has been both impressive and expensive. The crowd (myself included) appreciated her honesty throughout the conference, which in some way allowed expectations for student success outcomes to fall back to a reasonable level. That’s necessary for change. Realistically, most colleges can’t all secure the money needed to fund their own ASAP program and match CUNY’s three-year results.

Behavioral economics in action: Avoiding fight and flight with empathy and language

College leaders can guide students towards optimal decisions during onboarding and the rest of their academic careers by investing in the language and frame in which choices are presented. This is guided by the behavioral economic theory of choice architecture, which says that the decisions humans make are influenced by a set of contextual constraints, like language, design, or other available options. Below are a series of difficult situations students encounter during onboarding, their reaction to the situation under typical circumstances, and strategies to reduce the associated stress. Using these strategies, you can anticipate students’ needs and help them feel secure at your institution by removing the perception of threat to their enrollment goals, avoiding a fight-or-flight response altogether.

More Resources

58 student survey questions for community colleges

Pushed to the Brink: The Student Success Challenge at Elite Universities