How one university overcame two natural disasters

Education leaders everywhere are making fast, difficult, and bold decisions. That’s why we’re launching Leadership Voices, a series on leaders who meet extraordinary challenges with vision and courage.

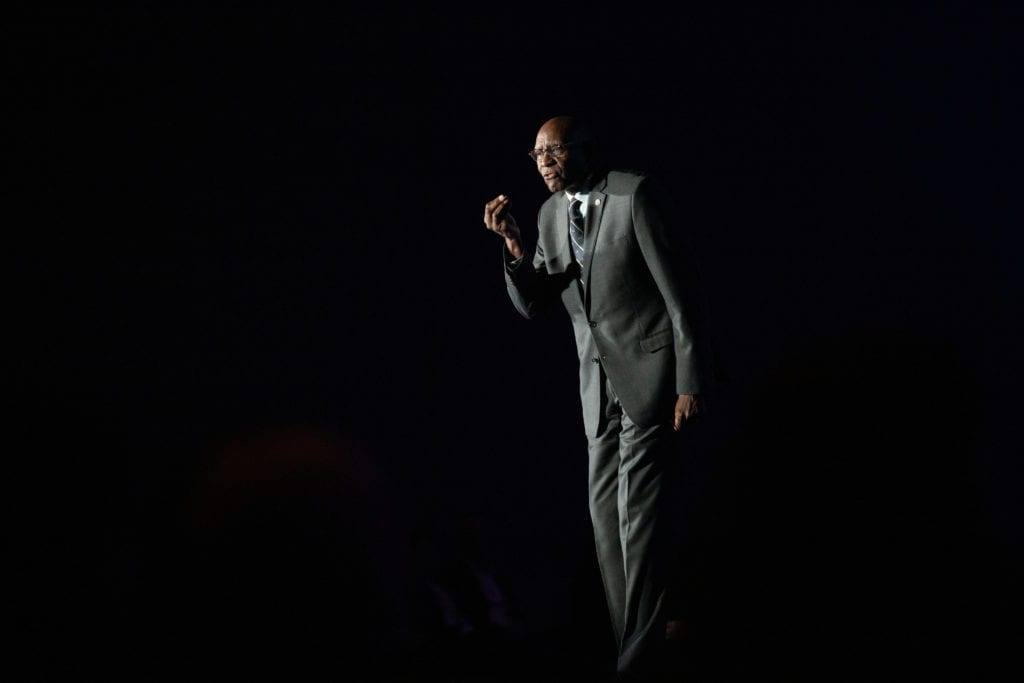

By Dr. David Hall, president of the University of the Virgin Islands

I’ve had the privilege of being the President of the University of the Virgin Islands for 10 years. In 2017, the University of the Virgin Islands was in a period of tremendous growth. During the previous eight years, we had added numerous new degrees, launched an entrepreneurship program, constructed two new buildings, set fundraising records, and started a study abroad program with Denmark funded by the Prime Minister of Denmark. We were on our way to reaching the next level.

Then, in September of 2017, our campus was hit by two Category 5 hurricanes within the span of two weeks, Maria and Irma. Winds of 185 mph swept through our campuses on St. Thomas and St. Croix, leaving trails of devastation and destruction in their wake. Our beautiful and scenic campuses looked like war zones.

The estimated damage to our campuses ranges between $60 million to $80 million. Ten buildings across both campuses were uninhabitable; faculty members lost their offices; students were deprived of classrooms, laboratories, a treasured residence hall; and so many aspects of college life were no longer present.

Once the hurricanes passed, our first concern was the wellbeing of our students, faculty, and members of our community. Then, our campus had to make tough decisions. Do we close the university down for the semester or do we press forward to make sure our students can continue their studies?

I gathered my cabinet and faculty members for a town hall meeting where I outlined a plan to re-open the campus within two weeks.

Funnily enough, not everyone was on board.

I remember that one faculty member stood up and said, “Let’s just stop. Let’s not try to come back.” This person had gone through a hurricane 20 years ago. She said, “20 years ago, we closed down the university for the rest of the semester. It delayed everything else, but by Fall we were able to get back on track.” When she said that, there was applause in the audience.

I responded, “If we do the same thing today, 20 years later, we’re not learning the lessons of the past 20 years. We have assets now that we didn’t have then.”

I understood the vulnerability of everyone in that moment. But I also understood the responsibility of a leader. In a moment of uncertainty, people need a level of certainty. Otherwise individuals would have left the room saying, “I don’t have to stay focused on this task because I don’t know what’s next.”

Rebuilding a campus

During my reflection about our plan for moving forward, I realized that a clear message to students about how we would support and treat them was essential. I developed and shared the principle of “holding them harmless.” Maria and Irma were not caused by my students, and so they should not suffer the consequences of them.

“Hurricanes Maria and Irma were not caused by my students, and so they should not suffer the consequences of them.”

– Dr. David Hall, president of the University of the Virgin Islands

The principle of “hold harmless” guided our perspective on how students should be treated during this major uncertainty. Students were given the right to withdraw without penalties, and faculty members were asked to be flexible and creative in how they conducted their classes and engaged our students. Faculty would not lower their standards, but instead raise their patience and increase their compassion. In the days, weeks, and months that followed, my cabinet, the Board of Trustees and I set out to lead students, staff, and faculty through these unprecedented challenges.

But this tragedy pushed us to demonstrate our academic resiliency. For example, our St. Thomas and St. Croix campus were without power and lighting and students couldn’t attend night classes due to an island wide 6 pm curfew.

So, our faculty members had to get more creative. Professors transformed their in-person classes to an online format, while others recorded their lectures so that students who missed class or couldn’t travel to campus could access the information. Our team was doing this while some professors had lost their homes and had no place to stay.

Students step up to the challenge

Students were just as part of the rebuilding efforts as our staff.

I remember the day I went to the residence hall where students had sheltered during the hurricanes. They had endured 36 hours without power or running water. Our staff needed to get bottled water into the facility and some of our students helped carry it in.

Other students were outside gathering rainwater so that the facilities could work. If you don’t have running water, you can imagine how the facilities might smell. Instead of pointing fingers at the administration, students did what they needed to do to make things work.

Other students had to shift their priorities in the wake of the hurricanes. During this period, we lost more than 10% of our student body. Some of these were individuals who took advantage of our “hold harmless” policy and had transferred to other institutions. For others it wasn’t about transferring, it was that college was no longer a priority because their families had been devastated by the hurricanes.

Despite these challenges, we were able to resume classes within a month after the first hurricane arrived. Through the creativity, resilience, and dedication of our faculty, administrators, and students, we were able to save not only the semester but also the academic year for our students.

How to lead through uncertainty

Your institution may not have to prepare for a natural disaster like a Category 5 hurricane, but your campus has opportunities to deal with smaller challenges every day. And it’s important to create a culture where we see ourselves as leading with our heart as well as leading with our head. That makes a difference.

It may be a student who doesn’t have enough money to pay their bill or a student who must take time off to deal with a death in his family.

People are more dependent on you than you could ever imagine during a major crisis. What you say matters. Will you treat those students as a cash source, or do you treat them as a human being who need your compassion and empathy? How you respond to these small challenges prepares you for what to do when the major ones come. And they will come.

Editor’s note: Dr. David Hall, the president of the University of the Virgin Islands, delivered this talk at EAB’s 2019 CONNECTED conference. His speech has been lightly edited and adapted for the web by Kathleen Escarcha.

Watch Dr. Hall’s story below

More ways to support students during a crisis

3 ways to prevent summer melt—and why technology is more important than ever

Learn three strategies to help colleges and universities support student retention and prevent summer melt caused by COVID-19.

More Blogs

Student success as a revenue strategy in higher education

Career readiness can’t wait until junior year