Attack of the “Math Shark”: Why unfinished learning is a lurking threat to student success in the late 2020s

July 28, 2023, By Ed Venit, Ph.D., Managing Director

Students are no longer entering college with the same levels of academic preparation that we might have expected before the pandemic, one of the many ripple effects we face as a result of disruptions in high school learning. Academic and student success leaders tell me that they are particularly concerned with performance in foundational math courses and programs that rely heavily on quantitative reasoning such as business, health professions, and STEM.

There’s a prevailing hope that students will figure it out and things will eventually return to pre-pandemic normal. I see it differently. Recent middle school testing data shows us that we have a big problem lurking below the surface, an imminent yet largely underrecognized threat slowly swimming its way across the mid-2020s. So far, we have only been seeing glimpses, like a shark fin poking out of the water. When it finally bites, this “math shark” will have major impacts on college student success. We need to begin preparing for it now.

Why should we be concerned?

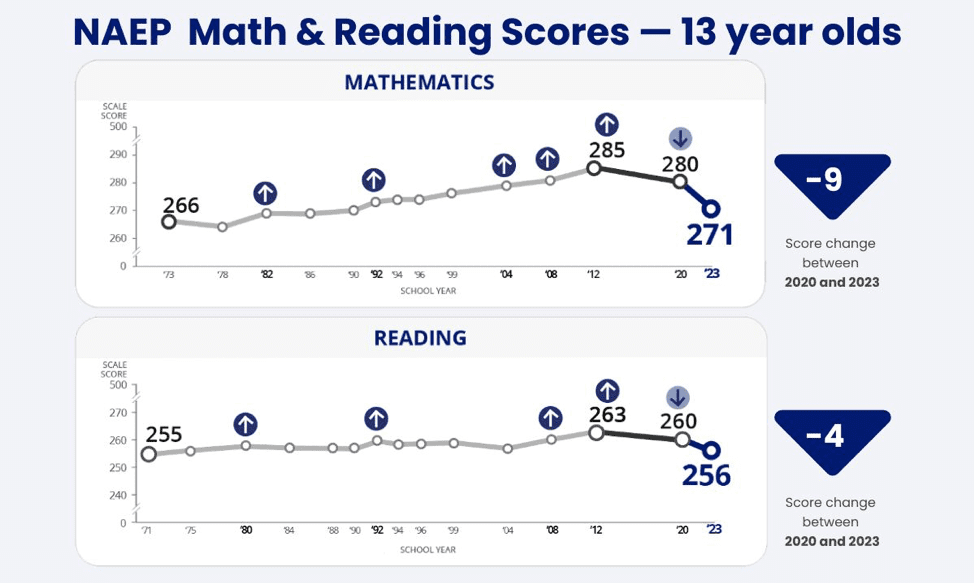

The pandemic has precipitated a steep decline in middle school math performance. Middle school math is closely monitored because it prepares students for high school algebra, a reliably strong indicator of later education outcomes. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) recently released their first post-pandemic look at the degree to which disrupted learning impacted 13-year-old math scores. Average scores fell to levels not seen since the 1990s, with score declines observed across nearly all geographies, socio-economic groups, and achievement levels, including the higher scoring students most likely to go to college.

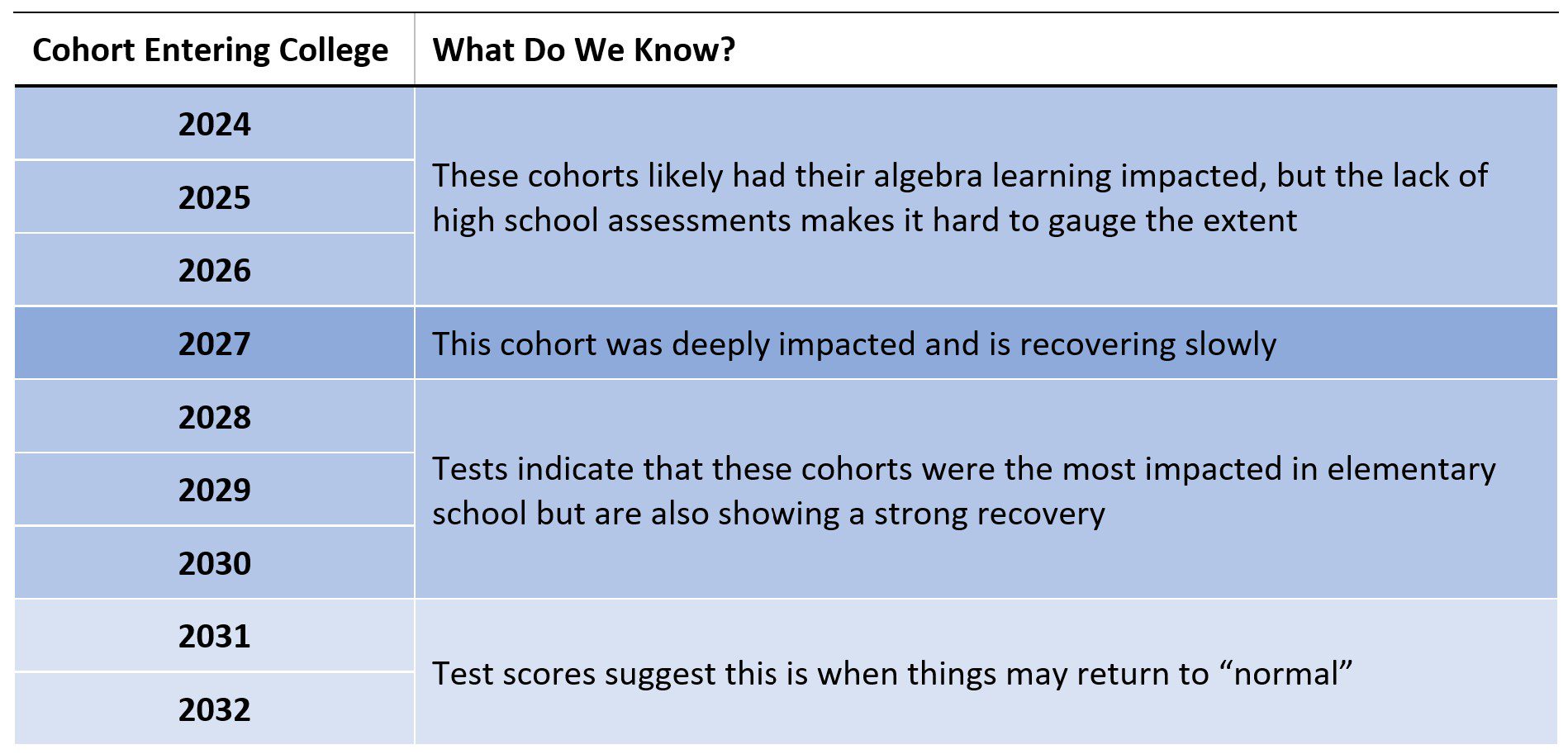

These students are not on pace to recover during high school. The non-profit NWEA has longitudinally tracked the rate of recovery for the cohorts of students who were in elementary school when the pandemic started. The class entering college in 2027 was in sixth grade in fall 2021 and has since failed to make up any of the ground they lost. NWEA estimates that at current pace it would take more than five more years for this cohort to recover to pre-pandemic levels for their grade year, well past their expected high school graduation date.

We need to prepare now for when this cohort begins entering college in four years. While most of the commentary on the NAEP scores has been rightly focused on what needs to be done to help K-12 students catch up, my attention has been on what happens when these students reach college age. Most of the 13-year-old cohort tested by NAEP in fall 2022 will enter high school in fall 2023 and begin entering college in fall 2027. Very few college leaders are talking about this right now, and most colleges and universities are not prepared to meet this wave. It is unclear what implications this will have, although I speculate on a few below.

Earlier cohorts may also be deeply impacted. The cohort of students who were taking algebra during their first year of high school in 2020-2021 will begin entering college in fall 2024. There are few national assessments of high school learning, so we don’t have a good sense of how well this cohort has recovered, if at all. If they are as deeply impacted as the years behind them, it is very possible that we will be feeling the effects of the math shark as soon as next year.

Long-term implications

Postsecondary institutions that do not heed these warning signs may soon be experiencing a math crisis that appears suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere. It’s likely that almost all schools will be impacted in some way, regardless of their selectivity, mission, student clientele, or geographic location. There will be big implications for enrollment and student success if we do not address this problem in the few years we have to prepare. Here are five speculations, although this is not a comprehensive list:

- Retention will likely be put under considerable pressure. Math has long been a stumbling block for college student success. Research during the pre-pandemic decade pointed to the detrimental impact of traditional math sequences on college persistence, especially among students of color and most pronounced among Black men. We should anticipate that the entering class of 2027 will arrive less well-prepared for math than any class in recent memory. It is hard to anticipate the degree to which this will affect retention rates or the demand it will put on academic support infrastructure, but it seems likely to be significant.

- Closing equity gaps may become even harder. Equitable college access and completion has been a major point of focus for the student success community for at least a decade, with good reason. NWEA found that the impact on elementary and middle school pandemic learning has been most pronounced among Black and Hispanic students. The underlying social inequities that drove pre-pandemic equity gaps have not gone away and are now being compounded by a political backlash. The NWEA data suggests that we cannot shrink from this important work and will have to put even more effort and resources toward equity initiatives going forward.

- It may become more challenging to demonstrate the value of college. Math is foundational to many high-demand degree programs, including Business, Health Professions, Computer Science, and anything else in STEM. Students struggling in math may not be able to pursue the degrees they want, which could in turn lead to greater attrition. Employers and state governments tie the value of college to the production of these high-demand degrees, meaning that the pandemic decline in math scores could make it even harder for colleges to demonstrate their value to taxpayers and the community.

- Declines in college participation could accelerate. In addition to creating student success challenges, the math crisis could have a big impact on incoming enrollment. An analysis by Harvard researchers found that changes in NAEP scores correlate with high school graduation and college-going behaviors. It should be noted that the same study did not find a significant correlation between NAEP scores and college completion, but then again, we have never been faced with a score decline of this magnitude.

- The demographic cliff could be much worse than anticipated. Math achievement will not be our only enrollment concern in 2027. The college entering class of fall 2027 will coincide with the start of the so-called “demographic cliff” that we have anticipated for over a decade. Pre-pandemic forecasts projected a 6-10% enrollment decline from 2027-2030 due to falling birth rates during the Great Recession. The intersection of this secular demographic contraction with the pandemic impact on learning suggests that these earlier forecasts may be overly optimistic.

How to get ready for what is coming

The entering class of 2027 may be smaller than expected, less well-prepared, less satisfied with their degree options, and less likely to persist. To be clear, this isn’t their fault. They missed out on crucial in-person learning during an unprecedented global event, and it is now our responsibility to ensure they have the best chance to catch up. Fewer students than ever will be college-ready—as we have traditionally defined it—so colleges must become more student-ready.

Fortunately, we know how to address this challenge. Two-year schools and open-access four-year schools have been innovating around math reforms for over a decade. Over the same time, data analytics tools and enterprise-level student success software have become powerful and ubiquitous. Together, these two advancements provide us a clear roadmap for how all schools can rethink their math strategy and fight off the “math shark.”

- Mine data to get a clear picture of where your current students stand on math. The math shark could already be here, and we just don’t know it yet. We lost many of our traditional math measurements during the pandemic. High school grades are no longer as reliable, standardized test scores became optional for admissions, and placement tests were often abandoned or replaced with alternatives. As a result, many colleges don’t have a good picture of how the math abilities of their current students have changed. The solution will be to develop new and more comprehensive dashboards that pull together all that is still known about students as they enter and combine it with their current performance in college math courses.

- Replace math placement tests with a “multiple measures assessment.” Traditional placement tests are clunky and high-stakes. They often don’t do a good job understanding the nuances of what a student has and has not mastered. The response has been to move to multiple measures assessment (MMA). MMA places students in math sequences by blending tests scores, high school grades, and non-cognitive elements. Advocates believe this results in more accurate placement and a better experience for students. Schools that have not done math placement before might consider how assessments could help them better understand their incoming classes.

- Build out co-curricular supplemental instruction to support increased demand for developmental education. Schools that have not paid much mind to developmental education may soon need to do so. Fortunately, one of the great advances of the Guided Pathways movement has been the conclusive research done on the negative impact of college algebra courses and the advancement of a far more effective alternative. Enrolling developmental students in college-level math while simultaneously enrolling them in a parallel cocurricular supplemental instruction course produces better outcomes and avoids delays in progress due to taking non-credit courses.

- Enroll as many students as possible in pre-college math boot camps. Boot camps can provide a benefit for all students and shouldn’t be thought of as remedial. For example, fully half of the entering class at the University of Nevada Reno participates in the NevadaFIT program. NevadaFIT students take a mini math course in the week prior to school starting. The program gives them a no-risk introduction to college math classrooms and support while building connections and help-seeking behaviors. UNR believes that FIT is responsible for eliminating their equity gaps in first-year retention rates across racial groups.

- Strengthen your math tutoring and academic support. This doesn’t just mean investing more in tutors and math labs, although this is likely to be necessary at many schools. Colleges also need to improve their ability to identify struggling students as early as possible and connect them to this support. Doing so requires intense cooperation between faculty, advising, and tutoring powered by an effective early alert and referrals system.

- Realign math requirements to their associated programs and majors. We should use this opportunity to reevaluate what kind of math learning is most beneficial to what students are studying. The traditional calculus sequence does not align well with majors outside of STEM and can often function as a student success barrier. In response, colleges have been expanding or altering math requirements to include statistics and quantitative reasoning courses that may be better aligned with the overall program curriculum. Of all the above recommendations, this is the one that will take the longest time and require the most consensus-building between administration and faculty.

4 Ways to Build Faculty Buy-In for Student Success Initiatives

We can change fast

Most college and university leaders will readily admit that their institutions do not change easily. Legacy mindsets, inflexible budgets, and a consensus-driven culture can impede progress. Yet, the early weeks of the pandemic showed that we can in fact change very quickly if we need to do so. The move online wasn’t pretty, and it certainly wasn’t painless, but we managed to make it work despite very little advanced warning.

Now we face another major threat, but we have some advanced warning this time. The math shark is lurking and could arrive at any point between now and fall 2027. The time to get ready is now. Meet with your team and your faculty to intentionally decide on a strategy, but don’t delay. Transforming college math won’t be quick or easy, and we need to get to work immediately.

More Blogs

Students need career support earlier. Here’s a scalable way colleges can provide it.

Student Success Blog

What the OBBB and the new Carnegie classification could mean for higher education accountability