8 Principles for Successful Budget Model Redesigns

Over the past decade, EAB has supported dozens of institutions redesigning their budget model. This includes campuses making a wholesale move from an incremental budget model to a more de-centralized one, those moving in the opposite direction to centralize parts of their model, and every type of model tweak in between.

Across these redesign efforts, we have identified eight principles most important to redesign success. EAB recommends all institutions changing models abide by the principles outlined below-regardless of current model, desired new model, or current point in the change process. You can click on any of the principles listed below to jump to that section and learn more.

- Complexity is the natural enemy of effective budget models

- Change is equally possible in periods of growth and decline

- Too many cooks too early leads to friction

- After go-live, stay the course for at least a few years

- Help your deans help you

- Don’t delegate all decisions to the math

- Choose your words carefully, as language can have an outsized impact

- Balance cost allocation design with discussions on service levels

1. Complexity is the natural enemy of effective budget models

The more complex your allocation formulae, metrics, or algorithms, the less transparent the model becomes, leading to weaker incentives and a lower likelihood to change behaviors.

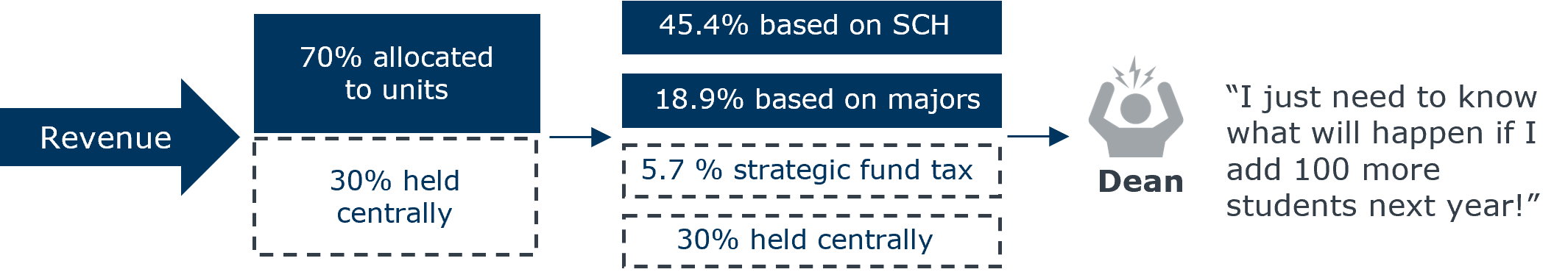

There are a number of rational design choices institutions can make, none of which are inherently ‘right’ or ‘wrong.’ For some institutions, it may make sense to hold back 30% of revenue to fund central operations, to separate international and domestic student tuition, or to allocate different indirect costs with different methodologies. In isolation, these choices may be reasonable. The challenge is if, in combination, they lead to over-complexity or unintuitive math.

Academic leaders should be able to intuitively understand the effects of adding 100 additional students to a certain program, for example. Model complexity weakens this connection, in turn weakening the incentive and the desired behavior change. University leaders cannot only consider design decisions in isolation. They must evaluate the cumulative impact of multiple decisions on the overall transparency and clarity of the model.

Incentives lose meaning with overly-complex allocation formulae

2. Change is equally possible in periods of growth and decline

Conventional wisdom to ‘only change models when you’re growing’ is outdated. Both growth and decline provide opportunities for stakeholders to rally around budget model change.

In periods of growth, there are often sufficient resources flowing through the system to satisfy everyone. Concerns about ‘winners and losers’ in a new model are less severe and shorter-lived with enough growth to go around.

Conversely, periods of decline provide an equally powerful burning platform for stakeholders to rally around. Although the ‘winners and losers’ dynamic is more acute, enough decisionmakers understand that change is necessary for the institution to succeed.

Rather, budget model change has proven hardest to justify in periods of business stasis. ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ sentiments are common. Leaders in this situation must work even harder to justify and demonstrate the benefits of change.

3. Too many cooks too early leads to friction

Core decisions for a budget model redesign should be made by a small group of senior leaders to avoid introducing politicking and finger-pointing early on.

Leaders should fight the instinct to bring in a wide range of stakeholders at the outset of a budget model redesign in the name of inclusivity or buy-in. Those working on the earliest stages of designing a new model must be selected based on their ability to problem-solve a complex financial situation.

Typically, this smaller group includes:

- President

- CBO

- Provost

- Budget Director

- Financially savviest dean

- Dean of the largest academic unit

- 1-2 college business officers (if applicable)

After this group has made the core model decisions, the institution can and should form wider budget model steering committees to make subsequent design choices, build inclusivity, and garner buy-in.

4. After go-live, stay the course for at least a few years

Beyond small and obvious ‘bugs,’ avoid making any changes to your budget model for two to three years after implementation to provide stability and consistency.

Small tweaks are likely necessary immediately after implementing a new budget model to address minor issues or ‘bugs’. Beyond small fixes however, set clear expectations that while stakeholders can report concerns, the model will not change for a minimum of two to three years. At that point, there will be a formal review period. This period of stability is critical to providing the model a legitimate test and allowing stakeholders time to learn and adapt to new incentives. In practice, many initial concerns disappear, as deans learn how to live in the new model.

Conversely, many institutions have found that making changes too quickly only invited more complaints and more changes, handicapping the model’s credibility at the outset.

5. Help your deans help you

Deans have varying levels of experience with budget models and may need guidance to succeed in a new model on day one. Equip them with the decision support and data they need to make successful decisions in their new roles.

Two categories of support are most important. First, deans often need additional financial staff support, both to learn the mechanics of the new model and to inform early unit budget decisions. Some institutions loan central finance team members to academic units as embedded business partners, while others carve out a portion of central finance’s time for dedicated office hours. Either approach can be effective, so long as deans have support when they need it.

Second, deans will likely need additional program-level and market data to compare program performance and make targeted investments and disinvestments. For more detail on providing the right-level data for deans, see the following EAB resources:

Partners often find that after a few years in a new budget model, deans begin asking for additional data to make more informed decisions. This is a positive sign that your model is driving desired behavior change. Our research on the Finance Function of the Future provides an overview of optimal business intelligence and strategic data infrastructures that will help drive better planning decisions.

6. Don’t delegate all decisions to the math

As your new model drives incentives to grow and take risks, central decision-making bodies are critical to safeguard against bad bets or short-term investments that cannot be sustained long-term.

Even in decentralized budget models, centralized planning processes are important to check against well-intentioned academic unit decisions. In fact, many of the most important central decision-making bodies are already relatively common. Leaders should ensure these structures are maintained, or even strengthened, during a budget model change.

Set of standard practices address majority of concerns

| Common Concern | Standard Solution |

|---|---|

| Academic units will launch unprofitable new programs | Central administration vets and approves all new program proposals |

| Units will make unnecessary investments in new staff | Provost retains power to approve all new full-time hires |

| Units will create low quality courses to poach students from other schools | Curricular Review Committee or Faculty Senate monitors course quality |

| Units will create duplicate courses to generate more revenue from their majors | Curricular Review Committee or Faculty Senate monitors course offerings for unwanted duplication |

| Units will make investments that deviate from institution-level strategic vision | Provost authorizes or denies dean reappointments |

Progressive institutions holistically regulate direct costs as part of central planning, collaboratively setting unit goals with individual deans and unit business officers. This ensures unit spending decisions are viable long-term and are in line with institutional strategy.

7. Choose your words carefully, as language can have an outsized impact

Deliberately changing budget vocabulary can help create a clean slate, and break associations with old, unpopular budget models.

No single set of words best describes the different components of a budget model. In fact, many institutions have seen meaningfully increased buy-in and support for change from simply choosing new budget models terms. Leaders admitted that many adjustments were change for change’s sake, but the resulting clean slate was critical to enabling productive early conversations.

Importantly, while this strategy might appear frivolous or inconsequential, it also has no cost or downside. In a world of limited resources and bandwidth, EAB encourages all leaders to consider this approach.

Sample terminology changes made by partner institutions

| Old Terminology | Possible New Terminology |

|---|---|

| Subvention | One university fund |

| Structural budget deficits | |

| Strategic investments | |

| Central tax | University fund charge |

| Strategic investment fund contribution | |

| Overhead tax | College share of expenditures |

| College contribution | Financial contribution |

| Weighted credit hours | Unique unit profiles |

| Allocation | Algorithm |

| Winners and losers | Contributors and mission-critical units |

8. Balance cost allocation design with discussions on service levels

Within a budget model change, discussions on indirect cost allocation are often the most contentious. As much as possible, focus academic unit leaders on administrative unit outputs and service over cost allocation methodology.

Inviting academic unit leaders to help craft administrative service level agreements (SLAs) during a budget model change has two key benefits. First, discussions on outputs and service act as a counterbalance to those on cost allocation and budget, which can quickly become negative and accusatorial. In fact, cost allocation has derailed changes at more institutions than any other part of the model re-design process.

Second, SLA discussions are typically more productive. Academic units have limited visibility into or understanding of central service budgets. They do, however, have experience with service outputs, and leaders can use model change as an occasion to ensure academic unit needs are being met.

This resource requires EAB partnership access to view.

Access the research report

Learn how you can get access to this resource as well as hands-on support from our experts through Strategic Advisory Services.

Learn More