Before layoffs and salary reductions, analyze these drivers of instructional cost

July 30, 2020, By Hersh Steinberg, Managing Principal, Office of the President

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, many colleges and universities have responded to the unprecedented financial pressure with extreme measures including pay cuts, furloughs, contract non-renewals, and even layoffs for faculty and staff. Given that instructional costs account for nearly half of institutional expenses, some institutions won’t be able to avoid these measures. But before reducing salaries or eliminating positions, administrators should determine how much savings they can achieve by effectively managing instructional costs and reallocating instructional resources.

Watch the video below to learn about different ways to approach cost containment.

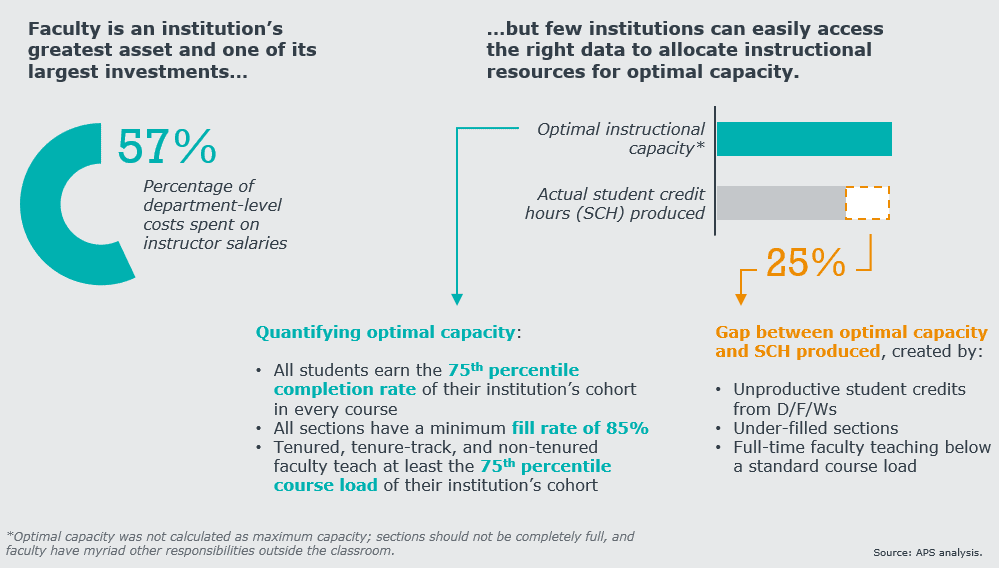

Currently, few institutions can easily access the data they need to allocate instructional resources efficiently, creating a gap between optimal capacity and actual student credit hours (SCH) produced.

To help you address these challenges, we’ve identified three ways institutions can manage instructional cost by re-allocating resources for optimal capacity.

1. Improve course completion rates

Over a third of unproductive credits occur in just 1% of all courses, many of which are gateway courses that most students must take. Unproductive credits cause course repeats, which can create devastating consequences for students’ academic progress and kick off a vicious cycle of bottlenecks term after term in these required courses.

College and universities can reduce the number of course attempts by targeting the 5% of courses in which 85% of repeats occur. Improvements in these courses build additional classroom capacity and extend faculty resources, which can then be used to further reduce enrollment bottlenecks and keep students on the path for on-time graduation.

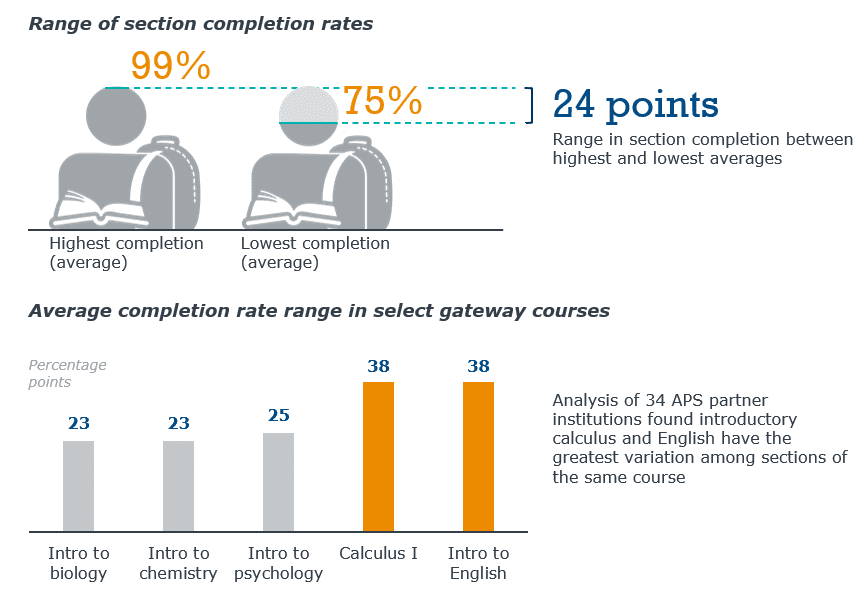

APS analysis also found a concerning trend in courses that have five or more sections: completion rates vary by 24 points on average. Lack of coordination and standardization across course sections leads to widely varied experiences and results for students—likely one cause of varied outcomes. Courses with a range in section completion rates exceeding this average should be investigated for potential improvement opportunities.

2. Ensure right-size section offerings

While students may find it difficult to enroll in gateway courses, many other classes are under-filled. Our analysis revealed 42% of course sections were found to have fill rates of less than 75%, meaning faculty time and classroom space invested in these courses are not being fully utilized. By consolidating low-fill multi-section courses, colleges and universities can reallocate faculty and classroom resources.

Similar opportunities exist to evaluate resources used for single-section courses. Courses with only one section comprise one-third of all course offerings, and one-third of those single-section courses have a fill rate below 50%. Despite low fill rates, these courses are seldom evaluated for necessity from term to term. While some single-section courses are necessary prerequisites or major requirements, institutions should regularly evaluate single-section course offerings to determine if they could be offered annually instead of every term.

-

42%

of course sections have fill rates of less than 75%

-

$550,000

on average, institutions could reallocate $550,000 in instructional salaries by offering low-fill single-section courses annually

3. Balance faculty course loads

Faculty spend a considerable amount of time outside the classroom advising students, completing administrative tasks, and conducting scholarly activities, among other duties, leaving less time available for teaching. In fact, we found that 50% of tenured and tenure-track faculty teach just three or fewer sections per academic year. While at some institutions this may make sense during the typical academic year, the COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented budget shortfalls which will demand reevaluation of institutional goals and priorities. Academic leaders need to consider whether these activities are still warranted in the face of today’s funding environment or whether there is an opportunity to optimize instructor workloads for increased student credit hour (SCH) production.

Review examples below to see the potential impact of two measures to optimize instructor workloads in high-cost departments:

Increasing history department median course load at a large research university

Institutions should increase the median course loads for tenured and tenure-track faculty, aiming to reach the 75th percentile of your department’s benchmark. For example, a history department at a high-research comprehensive institution exceeds their cost benchmark by $73 per attempted SCH. Their tenured and tenure-track faculty teach a median of two sections per semester, while their peers teach three. If they were to at least match the median teaching loads, increasing median loads by just one section, they would see a $23 reduction in instructional costs per attempted SCH.

Increasing introductory biology section size at a regional comprehensive institution

Increase large, multi-section courses by a few students each, where possible. An introductory biology lecture at a regional comprehensive institution, for example, could decrease the number of sections offered by three if the class size of each section was increased by just five students.

Explore 500+ Cost Containment Strategies

In closing

As COVID-19 infection rates increase in many parts of the country, we anticipate new challenges at colleges and universities across the country. Many institutions have been directed by their states to prepare for significant funding cuts. Never has it been more important to isolate and resolve inefficiencies to prevent unnecessary cuts. Limiting unproductive credits, reducing the number of under-filled sections, and maximizing instructional loads can help close the gap between actual and optimal SCH production, ensuring institutions are making the most of instructional resources.

More Blogs

4 reasons your university should invest in a permanent process improvement team—and how to maximize its impact

Higher education’s top cost savings opportunities