The demographic cliff is already here—and it’s about to get worse

With dire predictions for fall freshmen enrollments making headlines, colleges and universities are bracing for the financial shock to come. While many are hopeful that even a partial reopening of campuses in the fall will avert worst-case revenue scenarios, they still face a fiercely competitive domestic enrollment market.

It was already going to be a tough year, even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. Colleges and universities had been bracing for a much-feared “demographic cliff”—a steep drop-off in potential first-time full-time freshmen projected to arrive in 2025-2026. But last year there were signals the cliff had started to arrive early: even elite institutions ended up admitting more students from applicant pools and waitlists just to meet tuition revenue goals. Meanwhile, with the pandemic upending both K12 education and college-going plans, competition for first-time, full-time undergraduates will only get worse. Institutions scrambling to make up international student shortfalls and new NACAC rules that allow schools to recruit students at all times are only part of the problem.

Remote Instruction Will Likely Lead to a Spike in High School Dropouts

Last year, 1.2M students dropped out of high school. This year there are signs that number could be much higher. While the students most vulnerable to dropping out are in many cases those least likely to enroll in college, institutions with a mission to reach historically underserved populations and those reliant on rural populations will feel the impacts:

High Rates of Absenteeism

Early reports have shown that in some cases only half of K12 students are logging into their Zoom classrooms, with the lowest rates in rural areas where both students and their teachers lack reliable internet access. Under normal circumstances missing a limited number of classes can have a profound impact on student graduation. A recent study from Brown University found that missing ten days of math class reduced the likelihood that students would graduate by six percentage points, and reduced the likelihood that they would enroll in college by five points. If some high school students aren’t logging in to class at all, we can expect lower graduation and college-going rates during the pandemic.

K12 Students Less Successful in Online Classrooms

Even when K12 students do log into online classes, they tend to learn less than they do in person. A well-known study from Stanford University found that K12 students attending online schools were on average a half-year behind in reading and an entire year behind in math. Other studies of virtual charter schools have found that their students have consistently lower outcomes than in-person schools, even when controlling for the reasons students enrolled online. If students struggle in intentionally designed online classrooms, it’s reasonable to believe that high schoolers taught in hastily designed online classes are likely to be, at minimum, less academically prepared and may also be less likely to graduate.

Not just more students taking a gap year: many economic pressures thwart college-going

Recent surveys of students’ college-going plans have reported shockingly high proportions of seniors planning to delay enrollment (20% or more). But there’s reason to believe predictions about an increase in students taking a gap year are overblown. Even students who could afford the luxury of delaying their college education and graduation into the labor market don’t have many other options. Internships and jobs are scarce, and travel is off the table. More concerning is the impact of the economic downturn on the students and families who can least afford college.

Fewer Students Go to College When there are K12 Budget Cuts

Financial stress on districts from the current economic downturn will almost certainly depress college-going. Analysis of state K12 funding cuts during the last recession found that every $1,000 per-student funding cut resulted in a three-percentage point decline in college enrollment. With the current downturn already orders of magnitude worse than 2008 and state budgets facing crisis from increased healthcare spending and lower tax revenue, we can expect an even bigger impact on K12 funding and student college-going this time.

FAFSA Completion is Down

High school students rely on in-person reminders and assistance to complete the FAFSA. With K-12 schools closed across the country, FAFSA completions have declined significantly from last year, particularly among low-income and first-generation populations. As more families lose their ability to pay student tuition and expenses, not having access to Pell funding will have an even bigger impact on their ability to attend college.

No Signs (Yet) of More Government Incentives for Prospects

During the Great Recession, the federal government increased the maximum Pell grant award and raised the student borrower limit. In the current crisis there have not been similar incentives for prospective students to enroll, with CARES Act funding focused on minimizing financial impact to current students.

What do these trends mean for the next year’s class and the ripple effect to follow?

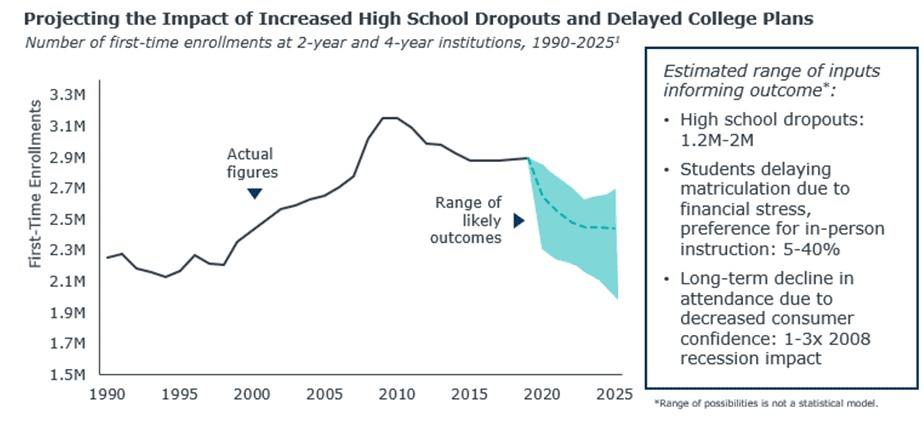

With these market signals in mind, EAB has developed a range of plausible outcomes for how first-time enrollment patterns could play out across 2-year and 4-year institutions. While we cannot predict the exact change in future first-time, full-time freshmen, anticipating the potential decline across sectors can help higher ed leaders prepare for the business model impact and the heightened competitive environment to come.

The top of the projected range above makes the assumption that most institutions will re-open for instruction in the fall, even if it is for remote instruction. Of the many surveys about students’ intent to enroll in the fall, the most conservative comes from Sallie Mae, which estimates that 10% of students will delay their college plans. If we were to take an even more conservative stance than that for the upper end of the projected range, then we could estimate that 5% of students will delay their plans and the number of high school dropouts will increase, but not significantly. The lower end of the range assumes major disruptions and shifts in consumer behavior. To arrive at this estimate we considered what the FTFT enrollment market would look like with an audience that is much less interested in paying for remote instruction and struggling with long-term financial stress to increase delayed enrollment all the way up to 40%. In considering what the worst possible outcome could look like, we also estimated what would happen if the high school drop-out rate tracked more closely with early reports of high school absenteeism during the pandemic. We think the likely path is somewhere in the middle of these optimistic and pessimistic outlooks, but even this shows an even steeper enrollment cliff this year.

The coming changes to the high school graduate population and college-going patterns represent just one of many interconnected threats to college and university business models. For an in-depth, data-based analysis of how Covid-19 will impact student success outcomes, net tuition revenue, and revenue diversification watch EAB’s on-demand Forecasting Impact of Covid-19 Virtual Keynote.

Featured Resource

Higher ed’s demographic future

More Blogs

5 steps graduate enrollment teams can take to reduce manual work

A day in the life of a prospective college student using AI in their search