Like most of you, the COVID-19 pandemic has completely upended my working life. The time I would normally have spent on airplanes visiting three or four campuses every week has instead filled with countless Zoom meetings, and there is no clear end in sight.

The question of when we’ll return to anything approaching “normal” has made me reflect on my experiences teaching change leadership courses and workshops. Over the years, I’ve taught leadership skills to nearly 1,300 chairs, deans, and provosts as well as rising managers at hospitals and healthcare systems. In that time, I’ve learned that, no matter the field, common principles guide successful individual, team, and institutional responses to uncertainty.

The US military has a helpful acronym that has been adopted in the fields of management and strategic leadership: VUCA. This describes situations characterized by:

- Volatility (an unknown rate and scope of change)

- Uncertainty (a lack of predictability)

- Complexity (interconnected and compounding issues)

- Ambiguity (open to multiple interpretations)

In this post I’ll outline three principles of responding to uncertainty. As the dust is settling on your immediate response to COVID-19, you have the chance to consider what you’ve learned so far and how to guide your team in the challenging months ahead.

1. Use reflection to guide your own response

A key practice of effective leaders during periods of uncertainty is the reflective pause.

COVID-19 resource center

Explore our latest insights to keep you up-to-date on higher education’s COVID-19 response

GoYou have been reacting nonstop. Before you respond further, pause for breath. This pause allows you to protect yourself against yourself. It gives you a chance to release the tension of the freeze, fight, or flee responses that you have been holding in your chest for the last couple of months.

After you catch your breath, you can identify and avoid extreme responses to better craft your balanced leadership response. Considering (and rejecting) the extreme reactions you might make, it is easier to craft a balanced leadership response.

The most memorable example of a reflective pause that I have ever seen came on the heels of another catastrophic event. On the morning of 9/11, as I arrived at work at the Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s foundation in downtown Chicago, the televisions in the conference room were already drawing us all in with unbelievable images from New York City. Fearing a possible repeat attack on the “Second City,” hospital administrators were activating the emergency response plan and informing us “non-essential” staff that we must stay put. We had no idea what would happen next.

The foundation’s vice president, who knew I was also an Episcopal minister, drew me aside as the TV programs were beginning to shift from news to commentary, and asked if I would be willing to help our own fundraisers and clerical staff as a sort of chaplain. As it happened, no one else called on me that day, but our brief conversation gave him the time he needed to center himself and move forward calmly, guiding us in our support of the frontline clinical staff.

How might you find time to allow your leadership team to “take a breath”? Perhaps it could involve giving the team a specific day (or even a half day) completely free from having to respond or act.

2. Guide your team’s response with gamification

Gamification in action

By experimenting with different formats, University of Central Florida staff realized minor changes to text message reminders could have a big impact on registration rates, “nudging” 70% of students to respond.

See How They Did ItYou have probably been scrambling—with phone calls, emails, town hall meetings, and constant communication—to help team members (who are grieving the loss of normalcy) come to terms with the current situation. But then what?

Coming to terms with the situation is not enough. Leaders often refer to the “five stages of grief” when discussing significant change, but that model ends with acceptance or resignation. When dealing with loss of the status quo in the workplace, we need to aim higher. We need team members not to be resigned but rather elevated, activated, and energetic—positively driving towards the future. And paradoxically, uncertainty itself can provide some of that energy.

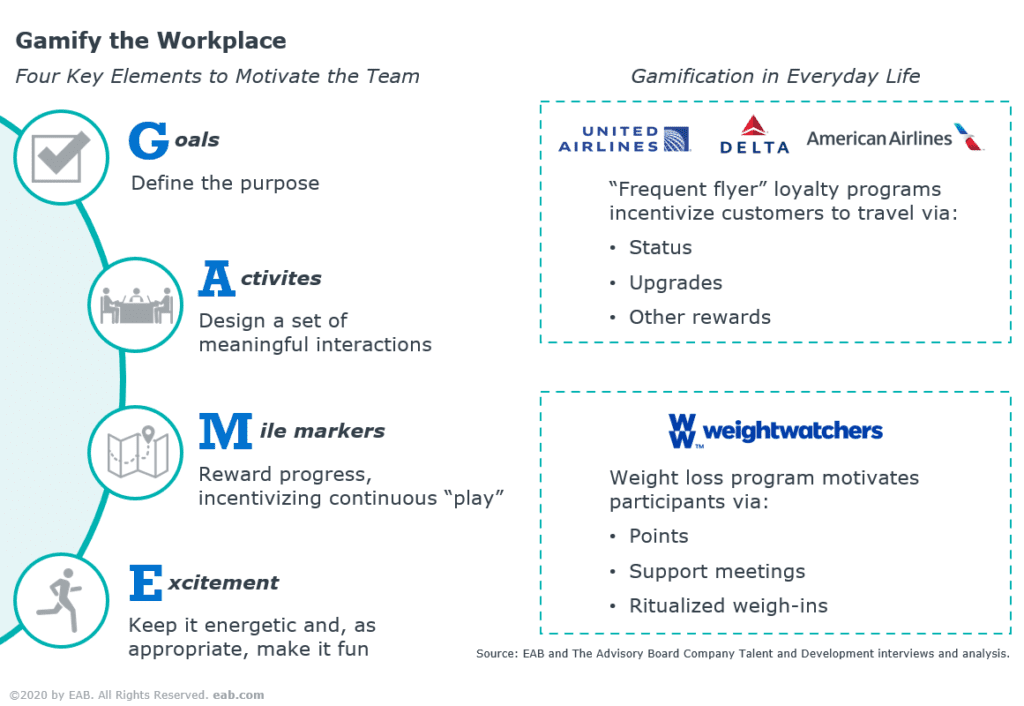

Gamification helps you use uncertainty to tap into staff members’ natural motivators. To do this successfully, four components must be present: goals, activities, mile markers, and excitement. I know “excitement” seems inappropriate during a global pandemic. Instead, in this context, think of it as energy—the energy that keeps your team engaged and motivated.

Providing opportunities to try new approaches, get immediate feedback on results, change tactics, and get energized and engaged is at the heart of gamification. And the uncertainty we’re all facing—Will this work? What about that?—can be a spur to your team to try new things. This approach may help your team tackle some of the many analyses campuses are undertaking to plan for the fall and beyond, or design new approaches based on the wealth of data generated over the last few months.

3. Guide your institution’s response with entrepreneurial thinking

In order to successfully navigate change, the whole organization needs to willingly engage with uncertainty and see the possibility in it. We need to value the next success and not be distracted by the old. We need to regard uncertainty as an opportunity for growth, not as a threat.

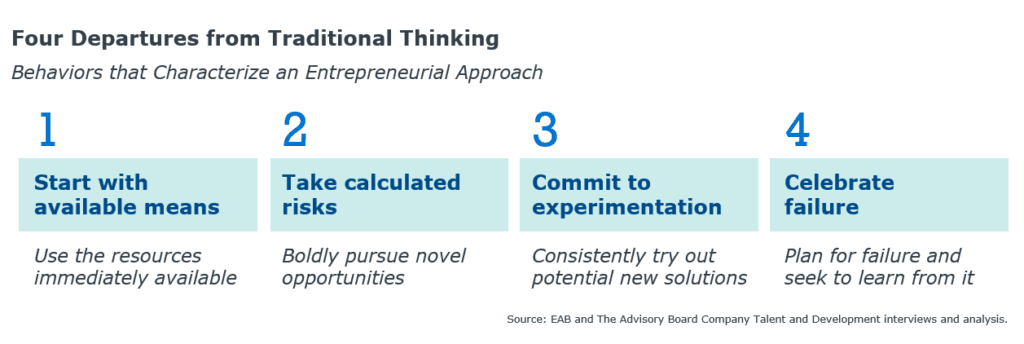

This isn’t simply an attitude shift. This is a drastic, but necessary, 180-degree strategic turn. Organizations cannot afford to run away from or avoid uncertainty. They need to be actively running towards it. But traditional problem solving, where you simply analyze your way out of a situation, leaves little room for innovation. When everything is uncertain, there are no right answers. That is where entrepreneurial thinking comes in.

In another part of my life, in which I serve as vicar of an Episcopal congregation, I’ve seen how difficult it can be for people to shift to an entrepreneurial mindset. As congregations and denominations grapple with changing patterns of religious belief and behavior, many have been guided by coaches like the Rev. Dr. Dwight Zscheile, an Episcopal priest who writes and speaks about countering cultural disruption with “faithful innovation.” He suggests a process of experimenting with ideas that respond to needs in the local community and (crucially) don’t cost any money. The idea is that lay and clergy leaders can try something new, but it doesn’t have to be forever.

In higher ed, our partners’ continuing and online education (COE) units are often hubs of entrepreneurial thinking. As units responsible for launching programs that meet rapidly-changing workforce needs, COE teams need to move quickly. One solution is testing program ideas in smaller “bites,” like individual courses or concentrations, to gauge audience demand. This way, they don’t lose much on what turn out to be inferior program ideas.

A problem I’ve often seen is that people get attached to the idea of disruption, or overturning the whole structure, rather than the work of innovation which is less dramatic but may lead to something new. The testing and rapid course-correction (that is, the faithful innovation) that characterize entrepreneurial thinking will be crucial to institutional success for the foreseeable future. Uncertainty around budgets and enrollments means spending time and money on things that aren’t working will no longer be an option. Colleges and universities will have to be more innovative, and make decisions at a faster pace, than ever before.

In closing

It’s critically important to learn from this moment. Working to get “back to normal” could mean resigning ourselves to grief—many colleges and universities were facing significant resource and success challenges before this pandemic hit.

After a reflective pause, leaders will need to guide their teams and their institutions through these uncertain times. You will need to release the creativity of your faculty and staff to play with new ways to engage and motivate students, to use data to identify particular cost saving opportunities, and to commit to bringing a spirit of “faithful innovation” to the decisions you’ll have to make together about what works and what doesn’t and what to try next.

You may also like

The impact of COVID-19 on institutional research and effectiveness offices

We surveyed 90 institutional research and effectiveness leaders to learn about the coronavirus's impact on their campus.

3 questions guiding fall term scenario planning for academic leaders

Explore 3 questions guiding fall semester 2020 scenario planning, and emerging trends in how colleges and universities are responding to the uncertainty.