The analysis you’re forgetting when evaluating your new program’s enrollment potential

We’ve all been there – you’ve had a great idea and you know, just know, everyone else is going to love it. Maybe it’s the murder mystery dinner party you hosted over Zoom during the pandemic lockdown, or maybe it’s the new degree you’re proposing to your academic development committee. But we can often misjudge how favorably others will react to our precious ideas. That’s a high-cost mistake to make when you’re committing resources to a new academic degree.

Costs of Unfounded Program Launch

-

Financial

Programs require significant resources to create and often involve ongoing cost commitments, as well (e.g., faculty lines, marketing partnerships)

-

Reputational

Struggling, underenrolled programs reflect poorly internally and externally, whether it’s making faculty skeptical of new program possibilities in the future or raising community concerns new programs won’t receive long-term support

-

Opportunity

In our world of limited resources, investing in one new program typically means not investing in another that perhaps could have had greater success

Developing well-supported enrollment projections can reduce the risk of new program launch and ensure you and your colleagues are prepared for what’s next.

Enrollment Projections Aren’t Always Accurate

We’ve come a long way since 2018 when our team was educating chief business officers on avoiding profitless growth with more rigorous new program planning. It’s now commonplace for new program approval processes to require business cases and enrollment projections. However, simply requiring proposals to include enrollment projections does not ensure those projections will reflect reality. Overly optimistic projections aren’t a sign of malintent, but they can be a sign that the proposer doesn’t have an objective view of the market, or just doesn’t have the expertise to develop good projections.

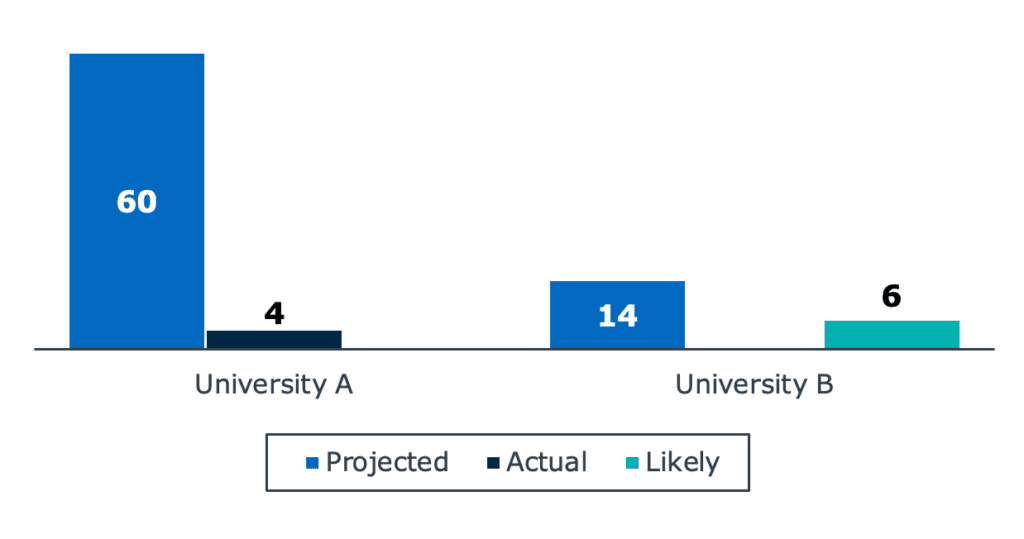

Years ago, we shared the unfortunate case study of University A, who launched a new specialized master’s in education projecting 60 students would enroll in year one—and only four students enrolled in the first cohort. Just this year, I found University B ready to make the same mistake with a specialized doctoral program. They projected 14 total students their first fall and eight graduates in their first class, reaching 18 by their fourth graduating class. A typical program in their state graduates six students a year, however, and their market is heavily skewed to a small number of large, dominant programs.

These proposal writers had the best interests of their colleges and students at heart but misjudged the market. This misestimation risked overinvesting in these new programs and setting impossible expectations for their early performance.

Here are two analyses to perform to create more realistic enrollment projections.

1. Use Degree Conferral Data for Competitor’s Program Performance as an Indicator

While imperfect, the Integrated Postsecondary Education Dataset (IPEDS) offers the most reliable insight into other programs’ performance at scale. Analyzing IPEDS degree conferral data allows you to consider:

- The median program size in your region and nationally

- How that median as trended over time

- Which schools offer the largest programs and how they’ve trended over time

Assessing these factors allows you to establish realistic enrollment projections. You can incorporate other factors into your projection, including qualitative ones like being the top-ranked school in your state or having access to a pipeline of undergraduate students who could stay for a proposed master’s degree, but this external perspective serves as a good check to possible overexcitement about program potential.

Degree conferral analyses work better for some programs than others: these analyses rely on Classification for Instructional Programs (CIP) codes to classify your program, and those codes don’t neatly match all possible offerings. If you’re evaluating a program that straddles CIP codes, or nestles within a broader category, you may need to adjust your approach to incorporate multiple program CIP codes. The resulting data will be less directly informative but can offer suggestions still – positive trends across all considered CIP codes would be encouraging at the least, whereas small or declining programs across all would require a strong case to expect your version to perform far better.

Two practices can further reduce the risk of enrollment projections when planning new programs:

- Consider a range of outcomes, not a single target. After establishing your best estimate, consider what would happen if you missed that projection by 25% as well as if you exceeded that projection by 25%. Planning with some “wiggle room” reduces the risk you’ll be caught off guard.

- Differentiate targets by their purpose. Use different points within your range for different planning purposes – your finance officer will want to know the budget works with your most conservative projection whereas your boldest goals can motivate your recruiters.

2. Leverage Multi-Dimensional Market Data to Evaluate Overall Demand Potential

Ultimately, remember projections and program evaluation shouldn’t ever rely on a single data source. You can draw on other sources of student demand and behavior data, such as counts of students self-designing a program because your defined offering doesn’t exist for them. Faculty can contribute perspectives on student desires or larger industry trends. Looking outside the institution, regional stakeholder input further bolsters program planning while labor market data offers an external, quantitative perspective on demand.

With the right analysis and preparation, your new program launch can be as successful as a Zoom-based murder mystery dinner party when you couldn’t go anywhere and had no other options (which is to say, a raging success, and context matters).

More Blogs

15 more campus visit tweaks that win over students

What Blockbuster can teach enrollment leaders about AI-powered college search